Oral administration, a common and convenient method of drug delivery, offers high patient compliance. However, oral drug absorption involves complex processes influenced by multiple factors: the drug’s physicochemical properties, dosage formulation, and physiological conditions of the gastrointestinal (GI) environment.

Beyond food-induced absorption delays, reductions, enhancements, or neutral effects, oral drug absorption is also pH-dependent. For example, SNAC enhances peptide bioavailability by a local increase in gastric pH. Key influencing factors include dissolution rate, solubility, intestinal permeability, and drug release positioning. Notably, wide gastric pH variations in large-animal PK studies critically impact experimental consistency. This article explores gastric pH regulation strategies for absorption optimization and shares solutions in large animal PK studies.

Case study: using cola to adjust gastric pH

To enhance oral drug bioavailability or reduce gastrointestinal irritation, medical advice or drug instructions often recommend taking drugs before or after meals. However, in certain cases, drugs like Posaconazole are taken with cola. Posaconazole is a broad-spectrum triazole antifungal used for preventing and treating invasive fungal infections. As a lipophilic weak base, its oral bioavailability is influenced by food and gastric pH. Research found that compared to fasting, drug absorption increases by 2.6 times with fat-free meals and 4 times with high-fat meals. However, patients receiving Posaconazole often have gastrointestinal damage and are prescribed acid suppressants, making it difficult to enhance drug absorption through meals. Additionally, variable gastric pH can lead to unpredictable drug absorption, affecting therapeutic outcomes. Therefore, researchers are exploring ways to improve drug absorption by focusing on researching gastric pH [1].

By comparing the effects of oral Posaconazole under four different conditions (Table 1), it shows that taking Posaconazole with cola alone results in higher Cmax and AUC0-48h values, indicating better absorption. In contrast, coadministration with acid-suppressants inhibits drug absorption compared to taking it with cola or water alone.

|

Condition |

Cmax (μmol/L)b |

AUC0-48h(μmol·h/L)b |

|

With 330mL water |

0.155±0.046 |

4.977±1.308 |

|

With 330mL Cola |

0.326±0.109 |

8.443±3.622 |

|

Acid suppressor for 3 consecutive days+330mL water afterward |

0.091±0.053 |

3.140±1.673 |

|

Acid suppressor for 3 consecutive days+330mL Cola afterward |

0.132±0.051 |

4.017±1.430 |

Table 1. Posaconazole Cmax and AUC0-48h values in plasma (n=5) a [1]

a Values are expressed in average ±SD

b 1 μmol/L = 700.8 ng/mL

The Influence of Gastrointestinal pH on Oral Drug Absorption

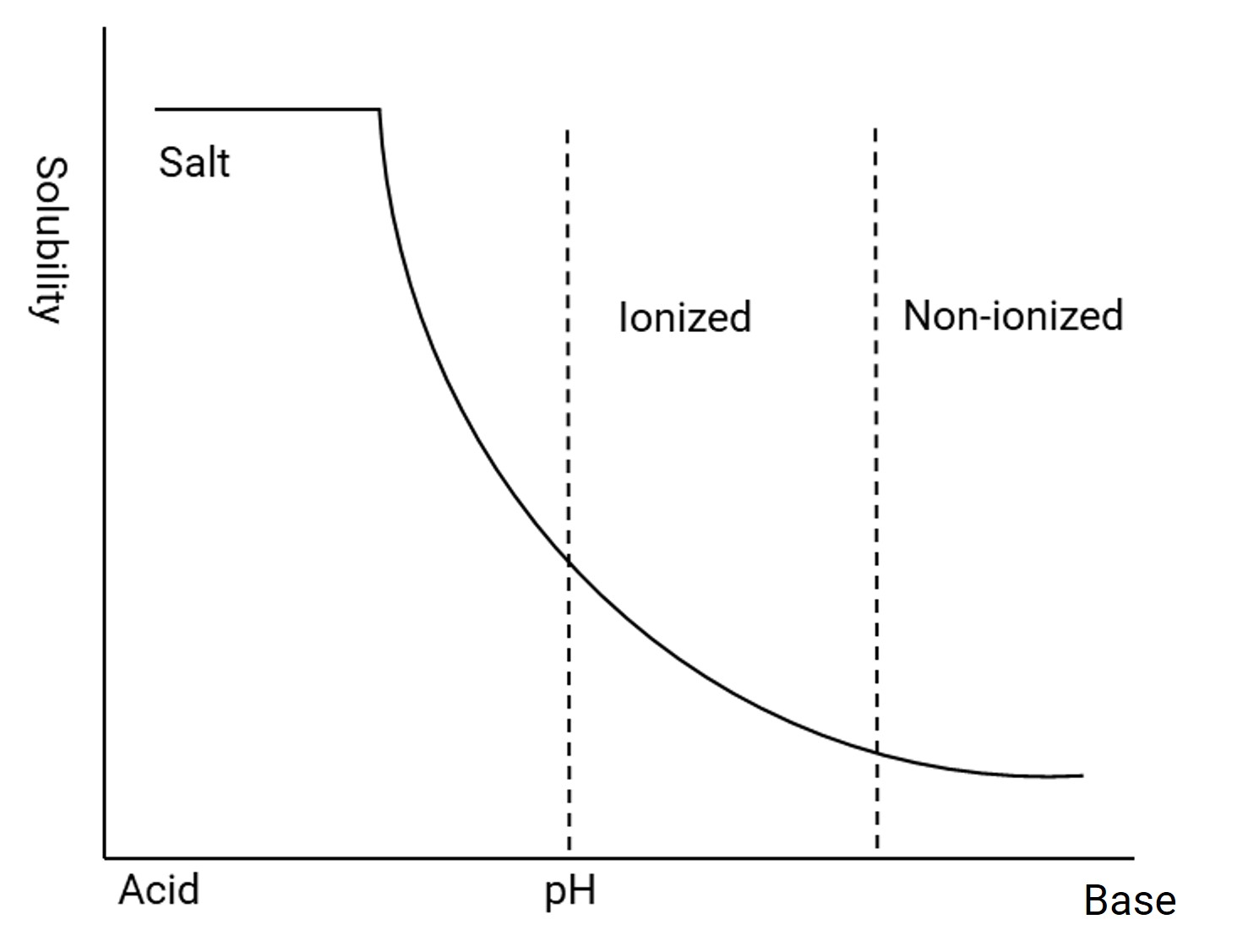

From the comparison of the above data, it is clear that gastrointestinal pH directly affects drug absorption. Oral drug absorption requires the drug to first dissolve and then pass through cell membranes to be absorbed by the body. Most compounds are weak acids or weak bases and exhibit pH-dependent solubility. For instance, weakly basic compounds have higher solubility in acidic conditions and lower solubility in base conditions (Figure 1), whereas weakly acidic compounds behave oppositely.

Figure 1. pH solubility curves for weakly basic compounds [2]

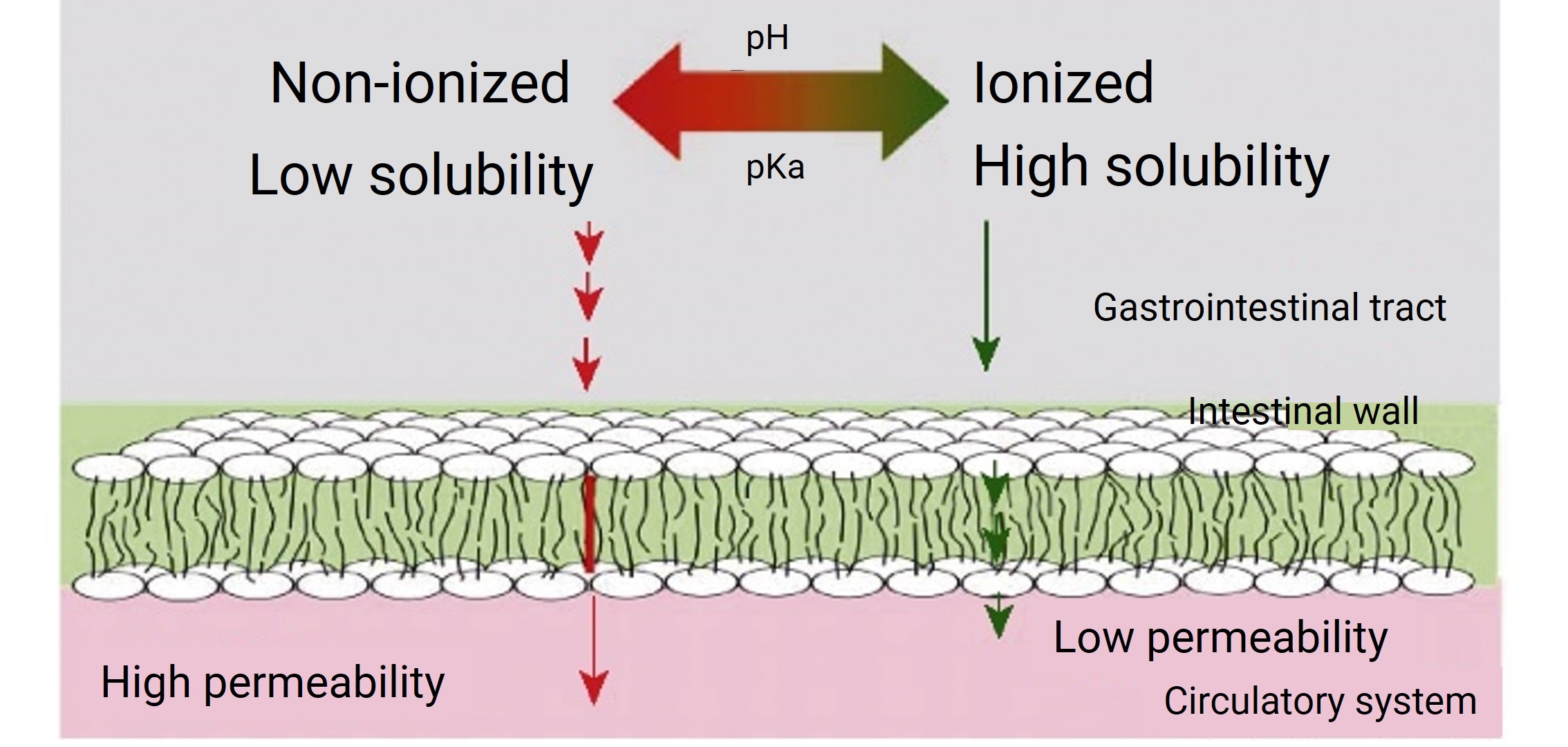

Additionally, the absorption of oral drugs primarily occurs through passive diffusion, which is influenced not only by the concentration gradient, molecular size, and absorption surface area but also by the permeability of the compound. Typically, weak acids and bases exist in both ionized and non-ionized forms after dissolution. Non-ionizable compounds are in an ionized state, have strong membrane permeability, and high permeability, whereas ionized compounds are charged, hydrophilic, and have low membrane permeability. Therefore, the proportion of un-ionized compounds, or the degree of ionization, determines the compound’s membrane permeability. Environmental pH and the compound’s pKa are crucial in determining the degree of ionization.

pKa (ionization constant) represents the pH when the concentration of ionized and non-ionized compounds are equal. For example, for a weakly basic compound (pKa=9), the ratio is 1:1 at a pH of 9. In base conditions, un-ionized compounds predominate, resulting in lower solubility but higher permeability. Conversely, in acidic conditions, ionized compounds predominate, leading to higher solubility but lower permeability (Figure 2). Weakly acidic compounds exhibit the opposite behavior.

In healthy individuals, the gastric pH is typically 1-2 when fasting, while the intestinal pH ranges from 5-7, indicating a gradual alkalization of the pH environment as the drug moves through the gastrointestinal tract. Although the stomach has a large surface area, its thick walls and short drug retention time limit absorption. In contrast, the intestines, with their villi, offer a larger surface area and thinner walls, facilitating easier drug permeation. Thus, oral drugs typically dissolve in the stomach and are absorbed in the intestines [4].

Figure 2. Drug pH-Dissolution-Diffusion Model [3]

Under normal conditions, weakly basic compounds dissolve more easily in the acidic environment of the stomach, but their solubility decreases upon entering the intestines. Conversely, weakly acidic compounds have lower solubility in the stomach’s acidic conditions but higher solubility in the intestines. When gastric pH increases, the solubility of weakly basic compounds in both the stomach and intestines decreases, leading to reduced dissolution and absorption in the body. On the other hand, the solubility and absorption of weakly acidic compounds are enhanced.

Therefore, when gastric pH is elevated, taking Posaconazole (a weakly basic compound) with cola (pH=2.5) can increase its solubility in the stomach. Additionally, researchers have found that cola can prolong the retention time of the drug in the stomach compared to water, further enhancing the absorption of Posaconazole.

In summary, taking Posaconazole with cola can significantly improve drug absorption. Hence, researchers recommend avoiding the use of acid suppressants when administering this medication and instead suggest using cola to enhance its effectiveness [1].

Strategies for adjusting gastric pH in preclinical PK studies

Choosing the appropriate species

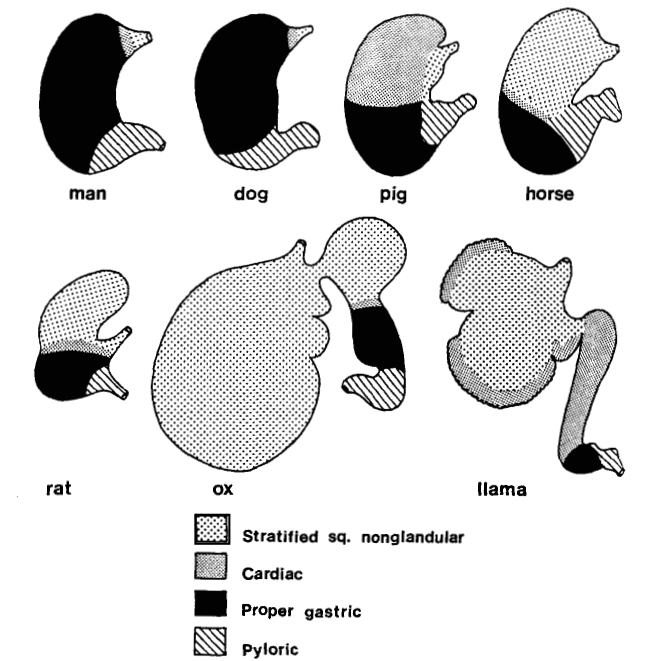

While the absorption of compounds can be predicted using in vitro methods like simulated gastrointestinal fluids, cell models, and isolated intestinal tissue models, in vivo animal studies are still essential for validation. No species perfectly mimics the human gastrointestinal traits, but by comparing the gastric morphology (Figure 3) and functions of various mammals, we find that dogs have a gastric structure very similar to humans. Their gastric emptying half-life and other gastrointestinal physiological parameters are also comparable to humans (see Table 2). Thus, dogs have a distinct advantage as an experimental species for oral drug administration [5].

Figure 3. Diversity of types and distributions of gastric mucosa in different mammals [5]

|

Parameters |

Human |

Dog |

Monkey |

Pig |

Rabbit |

Rat |

|

Stomach capacity (L) |

1-1.6 |

1 |

0.1 |

6-8 |

0.15 |

0.001 |

|

Small intestine length (%) |

78 |

85 |

- |

78 |

61 |

- |

|

Cecum length (%) |

3 |

2 |

- |

1 |

11 |

- |

|

Colon length (%) |

19 |

13 |

- |

21 |

28 |

- |

|

Average intestinal Length (m) |

8 |

4.82 |

2.08 |

23.51 |

5.82 |

1.2 |

|

The average length of the small intestine (cm) |

5 |

1 |

1.2-2 |

2.5-3.5 |

- |

0.3-0.5 |

|

Gastric emptying half-life (h) |

2 |

1.5 |

2 |

10 |

12 |

- |

|

Fasting gastric pH |

1.4-2.1 |

2.7-8.3 |

Similar to Human |

2.7 |

1.9 |

4.3- |

|

Fed gastric pH |

4.3-5.4 |

3.4-5.5 |

2.8-4.8 |

1.6-1.8 |

1.9 |

3.1-4.5 |

|

Small intestine pH |

5-7 |

6.2-7.5 |

5.6-6 |

6-7.5 |

6-8 |

6.5-7.1 |

|

Applications |

- |

Gastric morphology/gastric emptying |

GI enzymes |

Colon |

Gut microbiota |

- |

Table 2. Comparison of GI parameters across mammals [5]

Comparative data indicates that although monkeys are closer to humans in many respects, the high cost of experiments and limitations in oral capsule/tablet administration present challenges. Larger capsule sizes cannot be used for standard-sized monkeys, and monkeys often show low compliance during capsule administration. Pigs exhibit even lower compliance during oral administration, and continuous restraint and blood sampling are more challenging. Rabbits have thin stomach walls, lack specialized functional divisions, and exhibit coprophagy. Fasting tests reveal that even after 24 hours of fasting, chyme remains in rabbits’ stomachs. In contrast, dogs do not have these limitations.

Methods and cases for adjusting gastric pH in dogs

Although dogs are suitable for oral administration experiments, the wide range of gastric pH fluctuations in fasting dogs can impact experimental results. Studies [6] show significant variations in gastric pH in six dogs over ten experiments (Table 3): an average of 5.64, with a minimum of 1.36 and a maximum of 7.63. These data indicate considerable intra- and inter-dog variability in gastric pH, with a wide range of pH fluctuations that can impact the absorption of pH-dependent drugs. In experiments, issues such as significant within-group data variability and low oral bioavailability are frequently encountered, particularly for drug formulations that rely on pH changes for release, such as enteric-coated capsules, which remain stable at pH < 5 but release at pH > 5. If the gastric pH in the dog’s stomach is more alkaline, it may cause premature release of the enteric-coated capsules, preventing the collection of ideal data.

|

Day |

Dog 1 |

Dog 2 |

Dog 3 |

Dog 4 |

Dog 5 |

Dog 6 |

Mean (SD) |

|

1 |

7.28 |

7.15 |

6.58 |

2.32 |

3.63 |

6.34 |

5.55(2.07) |

|

2 |

7.63 |

5.28 |

5.67 |

2.2 |

4.16 |

6.9 |

5.31(1.95) |

|

3 |

7.2 |

7.01 |

4.56 |

6.63 |

7.21 |

5.63 |

6.37(1.07) |

|

4 |

7.28 |

6.82 |

3.06 |

4.84 |

6.54 |

2.76 |

5.22(1.97) |

|

5 |

7.33 |

1.85 |

6.86 |

6.73 |

2.65 |

2.52 |

4.66(2.56) |

|

6 |

6.62 |

7.25 |

2.76 |

7.32 |

7.14 |

6.17 |

6.21(1.74) |

|

7 |

5.92 |

5.93 |

4.42 |

6.5 |

6.91 |

4.91 |

5.77(0.94) |

|

8 |

- |

- |

- |

6.73 |

1.36 |

4.95 |

4.35(2.74) |

|

9 |

- |

- |

- |

6.98 |

7.02 |

3.45 |

5.82(2.05) |

|

10 |

- |

- |

- |

7.34 |

6.5 |

6.03 |

6.62(0.66) |

|

Mean (SD) |

7.07(0.58) |

5.9(1.93) |

4.84(1.61) |

5.76(1.97) |

5.31(2.17) |

4.97(1.56) |

5.64(0.73) |

Table 3. Measurement of Gastric pH in Fasted Dogs [6]

Controlling the gastric pH levels in dogs can be achieved through two methods: intramuscular injection of Pentagastrin or administration of Famotidine. Pentagastrin stimulates gastric acid secretion, while Famotidine inhibits it.

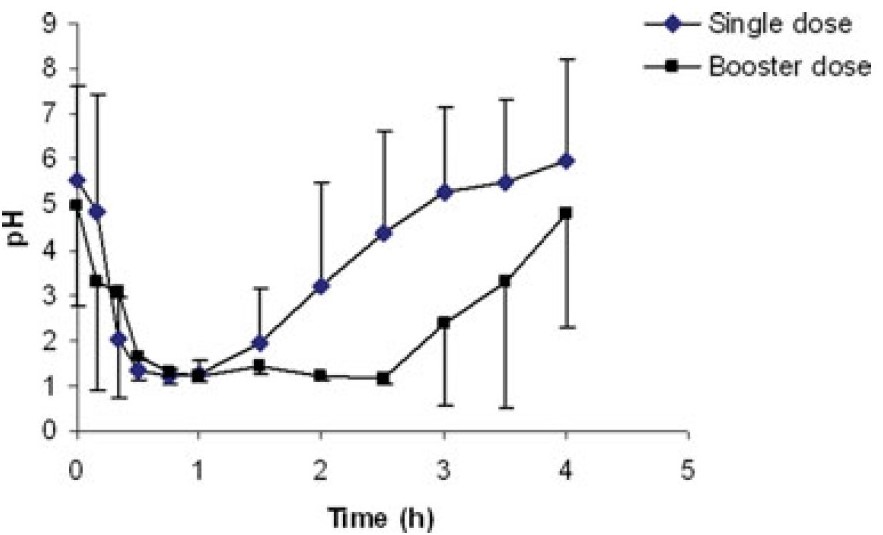

After treatment with Pentagastrin, the gastric pH in dogs can drop to below 2 within 20 minutes and maintain this level for 1 hour. If Pentagastrin is injected again after 1.5 hours, the gastric pH can be kept below 2 for an extended period (Figure 4).

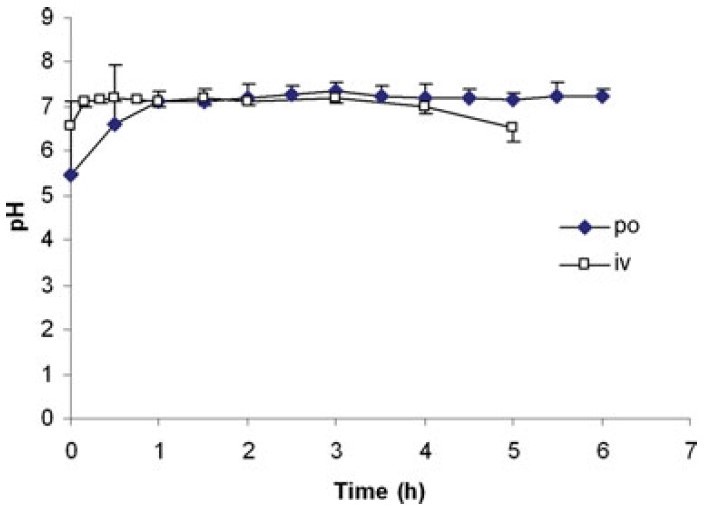

After treatment with famotidine, the gastric pH in dogs can reach 7 within 1 hour and maintain this level for 5 hours (Figure 5). With intravenous administration of famotidine, the gastric pH can exceed 7 within 10 minutes and remain elevated for 4 hours (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Canine gastric pH after a single pentagastrin treatment (6 μg/kg intramuscularly) and after a booster dose 1.5 h after the initial treatment [6]

Figure 5. Canine gastric pH after oral (40 mg) or intravenous bolus (0.5 mg/kg) administration of famotidine [6]

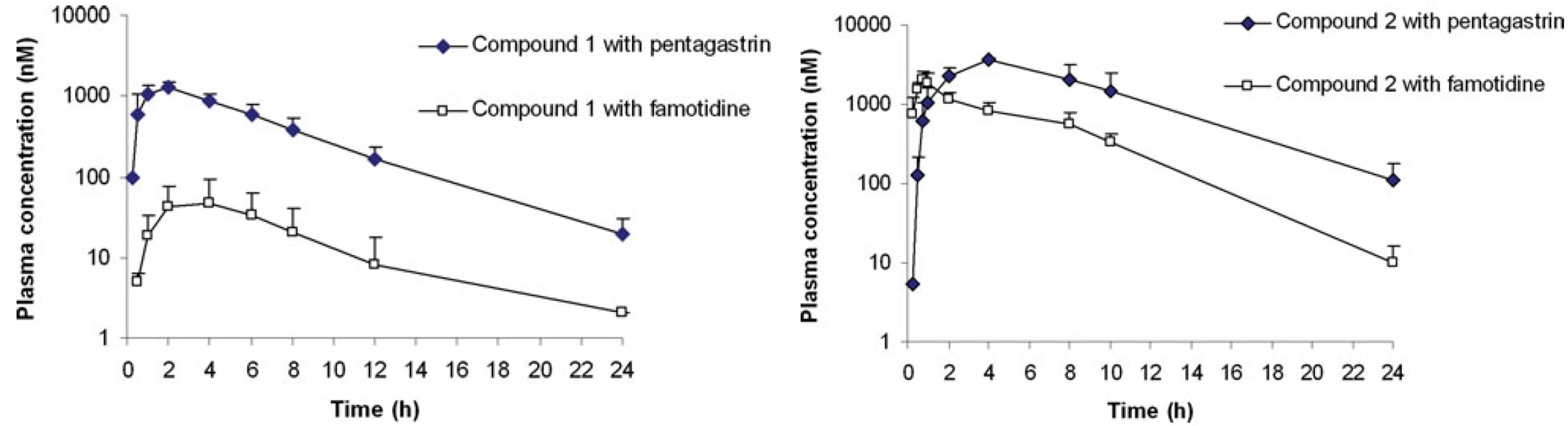

To further assess pH-dependent absorption, a study compared the effects of two different treatment methods on the absorption of two drugs. The experimental design involved administering two weakly basic compounds to the same three dogs. Prior to oral administration, the dogs received either intramuscular injections of Pentagastrin or oral Famotidine. The results are presented in Table 4, and the plasma concentration-time curves are shown in Figure 6.

The data reveal that both compounds exhibited higher Cmax and AUC values under Pentagastrin treatment compared to Famotidine treatment, indicating that these compounds are sensitive to changes in gastric pH. The difference was more pronounced for Compound 1.

|

Compound |

Pretreatment |

Cmax (nM) |

Tmaxa (h) |

AUC (nM·h) |

T1/2 (h) |

|

Compound 1 |

Pentagastrin |

1315(175) |

2.0(2.0-2.0) |

8249(1522) |

3.8(0.7) |

|

Famotidine |

49.3b(43.7) |

2.0(2.0-4.0) |

345b(348) |

4.1(1.1) |

|

|

Compound 2 |

Pentagastrin |

3631(262) |

4.0(4.0-4.0) |

30262(10359) |

3.8(0.2) |

|

Famotidine |

2060c(611) |

1.0(1.0-1.0) |

11893c(1959) |

2.8(0.5) |

Table 4. PK Parameters of compound 1 and compound 2 in Pentagastrin and Famotidine-Pretreated Dog [6]

a Given in the median number

b Statistically significant difference relative to Pentagastrin pretreatment (p < 0.05)

c P = 0.07 relative to Pentagastrin pretreatment

Figure 6. Effect of Pentagastrin and Famotidine pretreatment on plasma concentration-time curves of compound 1 and compound 2 [6]

Figure 6. Effect of Pentagastrin and Famotidine pretreatment on plasma concentration-time curves of compound 1 and compound 2 [6]

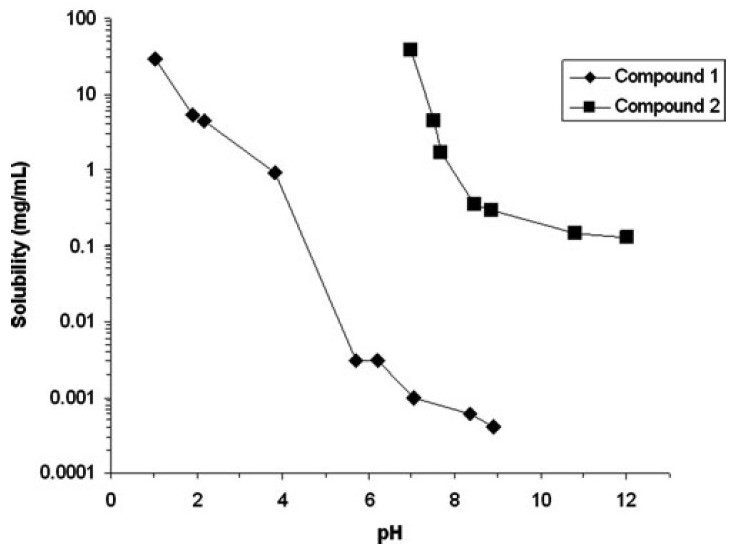

Under different pH conditions, the solubility test results for the two compounds varied significantly (Figure 7). At pH 1.1, the maximum solubility of Compound 1 was 29 mg/mL, while at pH 7.0, the maximum solubility of Compound 2 was 38 mg/mL. As the environmental pH increased, the solubility of both compounds decreased. The solubility test results show that the solubility of Compound 1 decreased more significantly than that of Compound 2 with increasing pH. This is primarily because Compound 1 has a lower pKa.

Figure 7. Effect of pH on the solubility profiles of compound 1 and compound 2 [6]

Conclusion

Gastrointestinal pH significantly influences drug dissolution, solubility, permeability, and absorption. While dogs are a valuable species for oral drug studies, their variable gastric pH can affect experimental consistency. To mitigate the variability in gastric pH, pentagastrin can be administered intramuscularly to fasting dogs, ensuring that their gastric pH closely approximates the levels observed in humans under fasting conditions, and this method enhances consistency in gastric pH across individual animals, thereby reducing the potential influence of gastric acid fluctuations on experimental outcomes. In combination with famotidine administration, efficient preclinical screening of compounds can be achieved, enabling researchers to identify pH-dependent characteristics and proactively address them, thereby minimizing the impact of gastrointestinal pH variability.

WuXi AppTec DMPK has extensive experience in gastrointestinal pH studies in dogs and monkeys, with the capability to interpret atypical oral drug data and a comprehensive methodology. Additionally, the large animal PK team is equipped with the capability to administer compounds to different intestinal segments, effectively mitigating the impact of gastric environmental factors on compound absorption, and this approach enables a more comprehensive study and comparison of absorption capabilities across various intestinal regions, supporting clients in achieving efficient and high-quality new drug development.

Authors: Chen Ning, Pengke Xia, Zhihai Li, Chao Zhang, Jacob Zhi Chen, Shoutao Liu

Talk to a WuXi AppTec expert today to get the support you need to achieve your drug development goals.

Committed to accelerating drug discovery and development, we offer a full range of discovery screening, preclinical development, clinical drug metabolism, and pharmacokinetic (DMPK) platforms and services. With research facilities in the United States (New Jersey) and China (Shanghai, Suzhou, Nanjing, and Nantong), 1,000+ scientists, and over fifteen years of experience in Investigational New Drug (IND) application, our DMPK team at WuXi AppTec are serving 1,600+ global clients, and have successfully supported 1,700+ IND applications.

Reference

[1] Jeroen, Walravens, Joachim, Brouwers, Isabel, Spriet et al. Effect of pH and comedication on gastrointestinal absorption of posaconazole: monitoring of intraluminal and plasma drug concentrations. [J]. Clin Pharmacokinet, 2011, 50(11): 725-734.

[2] Pallavi, Bassi,Gurpreet, Kaur,pH modulation: a mechanism to obtain pH-independent drug release. [J]. Expert Opin Drug Deliv, 2010, 7: 845-857.

[3] Zheng Hua, Hao Guizhou, Shang Pingping, et al. Prediction of Bioequivalence of Levatinib Mesylate Capsules Based on Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeation Model [J]. Chinese Journal of Modern Applied Pharmacy, 2024, 41 (13): 1775-1780

[4] Ahmad Y, Abuhelwa,Desmond B, Williams,Richard N, Upton et al. Food, gastrointestinal pH, and models of oral drug absorption. [J]. Eur J Pharm Biopharm, 2016, 112: 234-248.

[5] T T, Kararli,Comparison of the gastrointestinal anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry of humans and commonly used laboratory animals. [J]. Biopharm Drug Dispos, 1995, 16: 351-380.

[6] R Marcus, Fancher,Hongjian, Zhang,Bogdan, Sleczka et al. Development of a canine model to enable the preclinical assessment of pH-dependent absorption of test compounds. [J]. J Pharm Sci, 2011, 100: 2979-2988.

Related Services and Platforms

Stay Connected

Keep up with the latest news and insights.