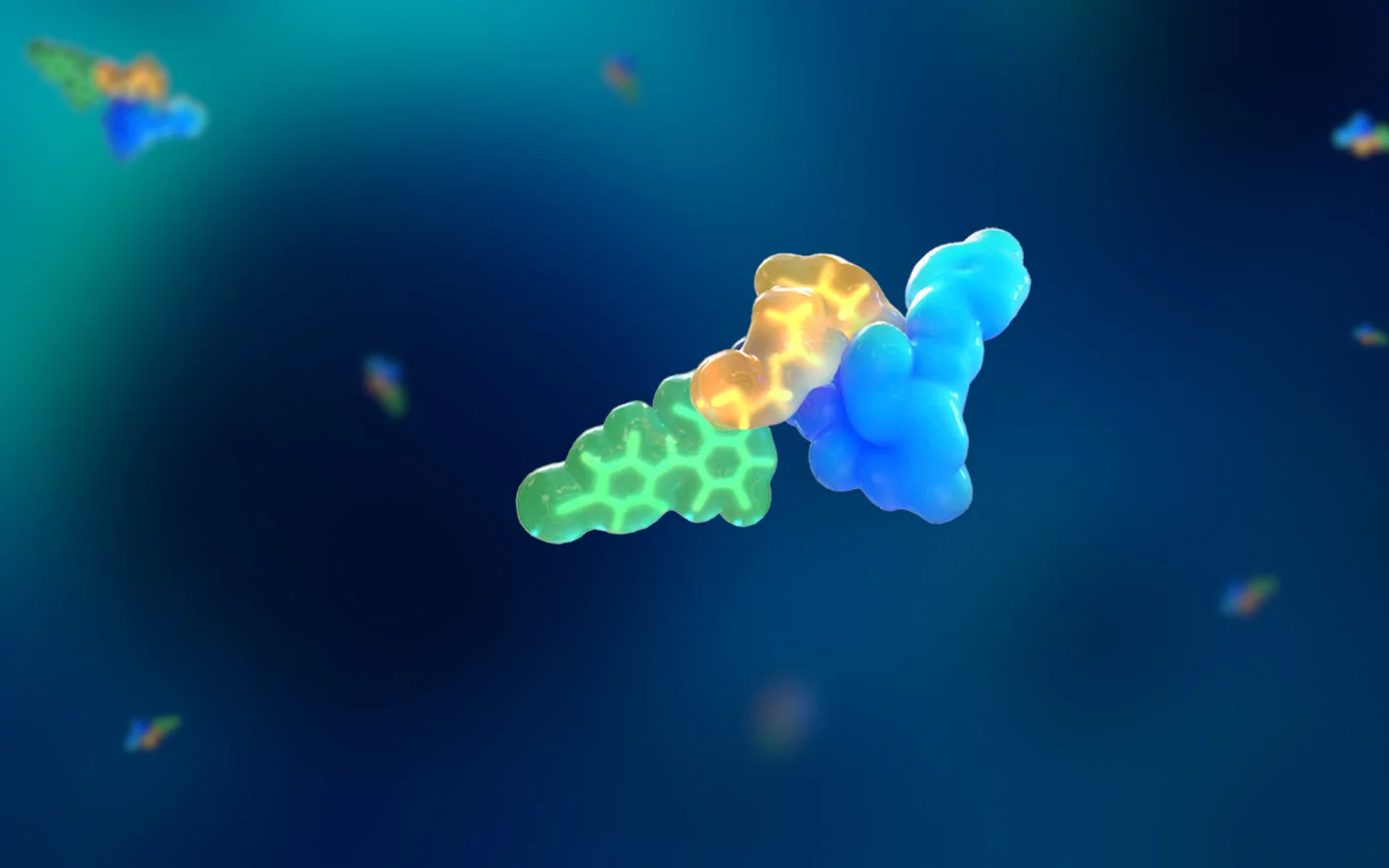

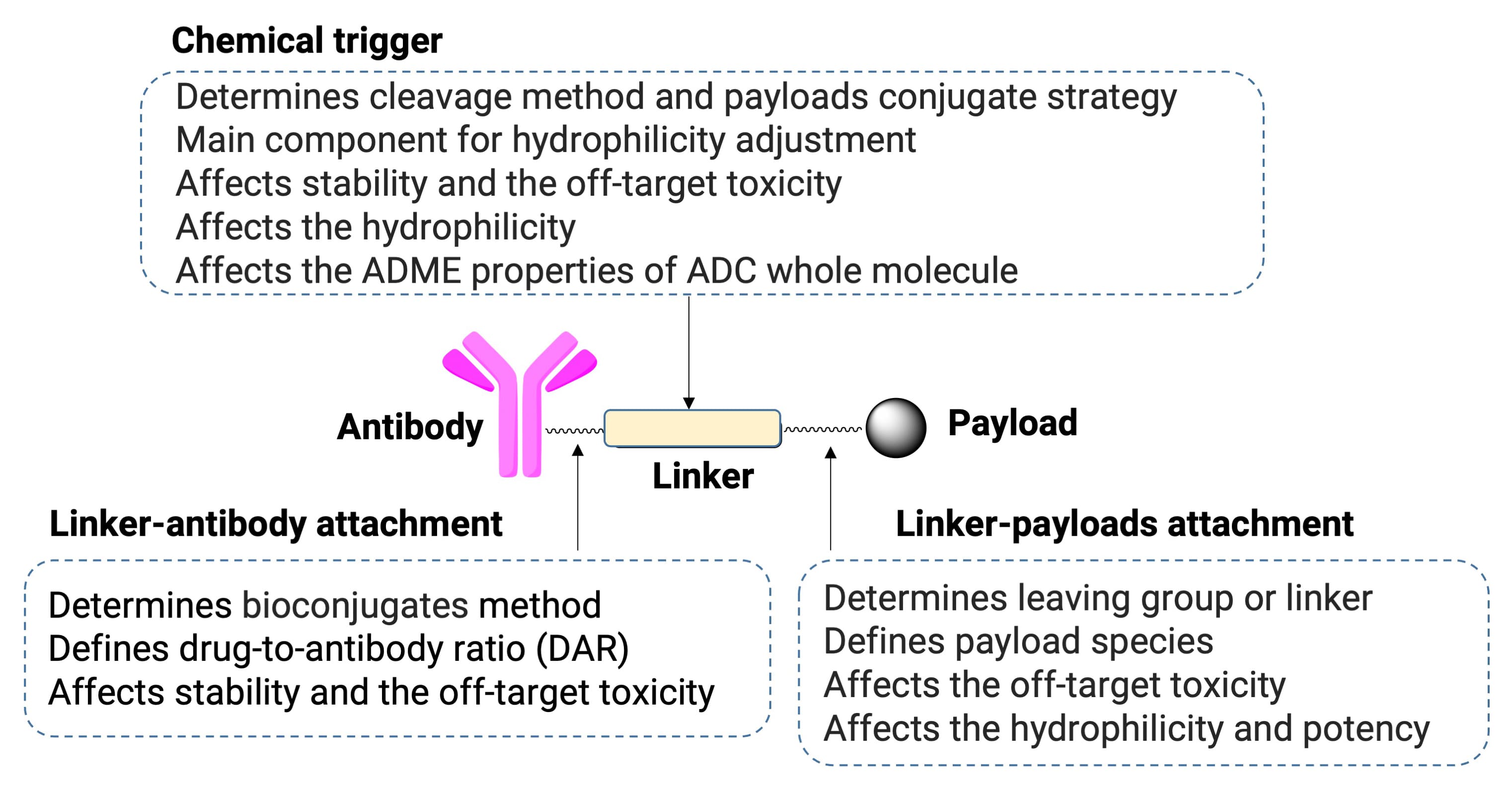

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represent a specialized class of targeted therapeutics formed by coupling specific antibodies with cytotoxic payloads via a chemical linker. Their success hinges on selective accumulation in target tissues and highly efficient tumor cell killing, requiring the ADC to remain stable in circulation to minimize off-target toxicity while releasing its payload in response to specific biochemical cues at the target site.

In their R&D, ADC linker design is a pivotal stage. The linker directly governs circulatory stability and payload release, acting as the fulcrum that balances efficacy with safety. This review discusses ADC linker design strategies, covering cleavable and non-cleavable linker types, functional groups for antibody conjugation, self-immolative spacers, and hydrophilic modifications. It further explores ADC DMPK in vitro evaluation methods for linker optimization, offering insights to support ADC efficacy, stability, and off-target toxicity optimization.

Figure 1. Typical structure and functional characteristics of ADCs [1]

ADC Linker Classification and Approved Drugs Overview

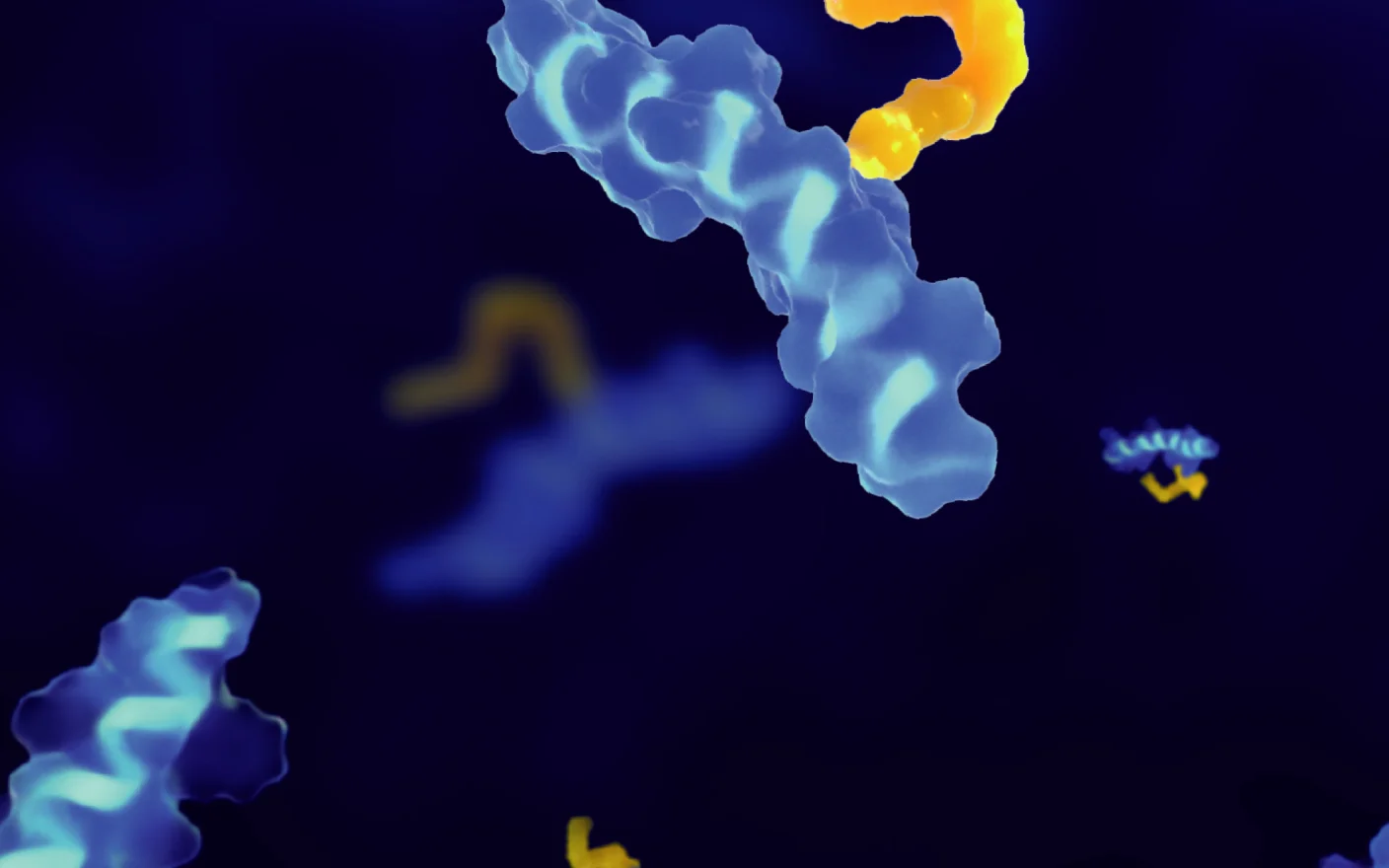

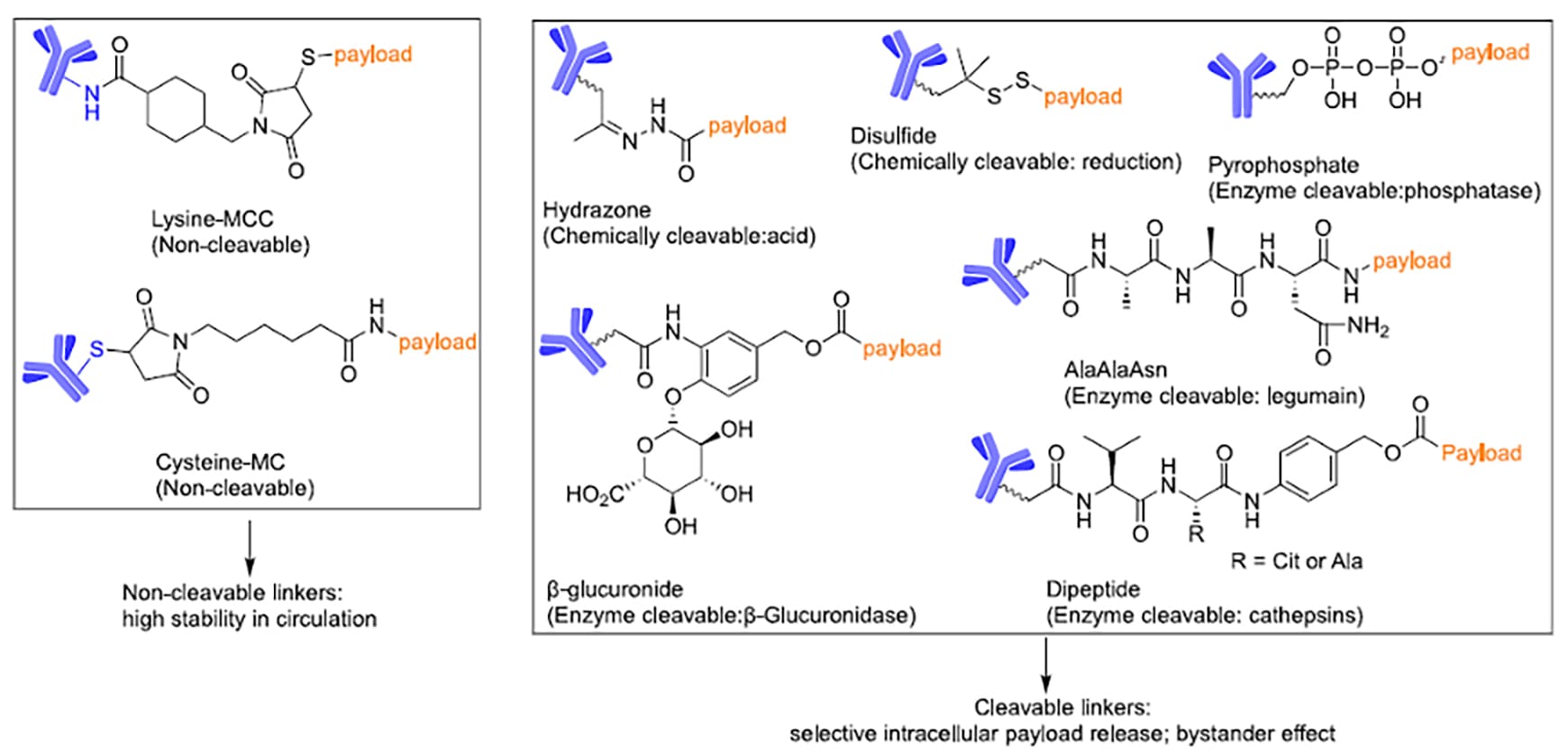

Based on the payload release mechanism, ADC linkers are primarily categorized into two distinct types: cleavable linkers and non-cleavable linkers (Figure 2).

Non-cleavable linkers (e.g., Lysine-MCC) are integral to ADC linker design due to their exceptional plasma stability. Upon internalization by the tumor cell, the antibody component is hydrolyzed by lysosomal proteases, releasing a linker-payload complex containing amino acid residues. Because this complex typically retains hydrophilic residues, it exhibits poor membrane permeability, limiting its cytotoxicity primarily to tumor cells that highly express the target antigen.

In contrast, cleavable linkers (including pH-sensitive hydrazone bonds, reduction-sensitive disulfide bonds, and enzyme-sensitive peptides) achieve controlled release by responding to specific biochemical triggers within the tumor microenvironment or cytoplasm. The released payload is usually hydrophobic and possesses strong membrane permeability. This enables the killing of not only the primary target cells highly expressing the target antigen but also neighboring cells with low or negative antigen expression via the "bystander effect," effectively overcoming tumor heterogeneity. This controlled release, combined with payload membrane penetrability, gives cleavable linkers a distinct advantage in solid tumor therapy.

Figure 2. Classification and chemical structures of ADC linkers [2]

As of December 2025, 21 ADCs have received global approval (Table 1). An analysis of these therapeutics reveals a dominance of cleavable linkers (17 approved), 12 of which utilize enzymatic cleavage mechanisms. This trend persists in clinical development, where over 50% of pipeline ADCs employ enzyme-cleavable designs. Clearly, cleavable linkers occupy a leading position in current R&D, with enzymatic strategies being particularly widespread.

Table 1. Overview of the 21 ADCs Approved by FDA/PMDA/NMPA[2]

First Approved | Drug Name | Trade Name | Target | Linker Type | Payload | DAR |

2000 (FDA) | Gemtuzumab ozogamicin | Mylotarg | CD33 | Hydrazone/disulfide | Calicheamicin | 2-3 (Lys) |

2011 (FDA) | Brentuximab vedotin | Adcetris | CD30 | MC-VCit-PABC | MMAE | 4 (Cys) |

2013 (FDA) | Trastuzumab emtansine | Kadcyla | HER2 | SMCC (Non-cleavable) | DM1 | 3.5 (Lys) |

2017 (FDA) | Inotuzumab ozogamicin | Besponsa | CD22 | Hydrazone/disulfide | Calicheamicin | 6 (Lys) |

2018 (FDA) | Moxetumomab pasudotox | Lumoxiti | CD22 | N/A | PE-38 | N/A |

2019 (FDA) | Polatuzumab vedotin | Polivy | CD79b | MC-VCit-PABC | MMAE | 3-4 (Cys) |

2019 (FDA) | Enfortumab vedotin | Padcev | Nectin-4 | MC-VCit-PABC | MMAE | 3.8 (Cys) |

2019 (FDA) | Trastuzumab deruxtecan | Enhertu | HER2 | MC-GGFG-AM | Dxd | 8 (Cys) |

2020 (FDA) | Sacituzumab govitecan | Trodelvy | TROP-2 | CL2A (Carbonate) | SN-38 | 7.6 (Cys) |

2020 (FDA) | Belantamab mafodotin | Blenrep | BCMA | MC (Non-cleavable) | MMAF | 4 (Cys) |

2020 (FDA) | Cetuximab Sarotalocan | Akalux | EGFR | Linear alkyl/alkoxy (Non-cleavable) | IRDYE700 | 1.3-3.8 (Lys) |

2021 (FDA) | Tisotumab vedotin | Tivdak | TF | MC-VCit-PABC | MMAE | 4 (Cys) |

2021 (FDA) | Loncastuximab tesirine | Zynlonta | CD19 | Mal-PEG8-Val-Ala-PABC | PBD Dimer | 2.3 (Cys) |

2021(NMPA) | Disitamab vedotin | Aidixi | HER2 | MC-VCit-PABC | MMAE | 4 (Cys) |

2022 (FDA) | Mirvetuximab soravtansine | Elahere | FRα | Sulfo-SPDB (Disulfide) | DM4 | 3.5 (Lys) |

2024 (NMPA) | Sacituzumab tirumotecan | 佳泰莱 (JiaTaiLai) | TROP2 | Modified CL2A | KL610023 | 7.4 (Cys) |

2024 (PMDA) | Datopotamab deruxtecan | Datroway | TROP2 | MC-GGFG-AM | Dxd | 4 (Cys) |

2025 (FDA) | Telisotuzumab vedotin | Emrelis | c-Met | MC-VCit-PABC | MMAE | 3.1 (Cys) |

2025 (NMPA) | Trastuzumab rezetecan | 艾维达 (AiWeiDa) | HER2 | MC-GGFG-AM | SHR9265 | 6 (Cys) |

2025 (NMPA) | Trastuzumab botidotin | 舒泰莱(ShuTaiLai) | HER2 | VCit | Duostatin-5 | 2 (Lys) |

2025 (NMPA) | Becotatug vedotin | 美佑恒(MeiYouHeng) | EGFR | MC-VCit-PABC | MMAE | 4 (Cys) |

Strategies for ADC Linker Cleavable Site Design

Chemically Cleavable Linkers

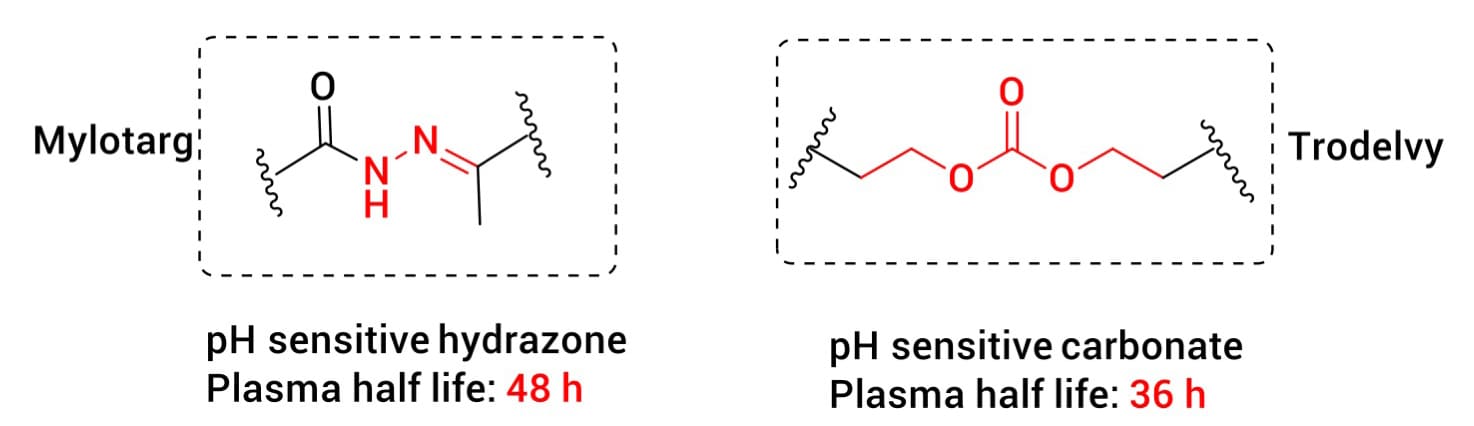

Early successes in ADC linker design often utilized pH-sensitive mechanisms. For instance, Mylotarg incorporates a hydrazone bond, while Trodelvy uses a carbonate structure (Figure 3). These linkers are designed to be relatively stable at physiological pH (~7.4) but undergo hydrolysis in the acidic endosomes or lysosomes (pH 4.5–6.0) of tumor cells. This approach exploits the pH gradient between plasma and intracellular compartments to achieve selectivity for payload release. However, pH-sensitive linkers can struggle with insufficient plasma stability, leading to premature release before reaching the target, which restricts their broader application.

Figure 3. Acid-cleavable linkers [1]

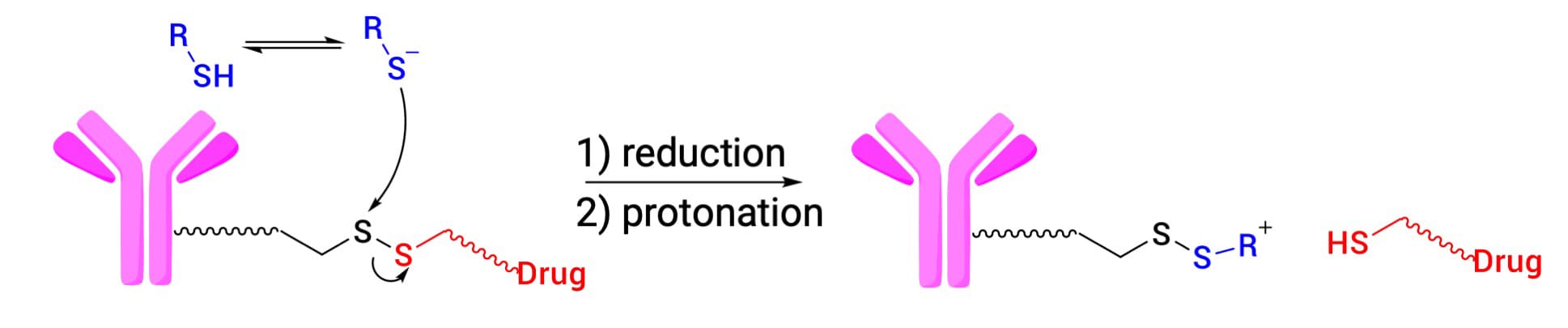

Disulfide bonds represent another critical category of chemically cleavable linkers (Figure 4), utilized in three approved ADCs (Mylotarg, Besponsa, and Elahere). Their cleavage mechanism relies on glutathione (GSH) concentration gradients: plasma GSH levels are low (2–20 μmol/L), whereas intracellular levels are significantly higher (1–10 mmol/L), particularly in tumor cells. This differential ensures the disulfide bond remains stable in circulation but is reduced and cleaved upon cell entry.

Effective disulfide design requires a fine balance between plasma stability and cleavage efficiency. Introducing methyl substituents on carbon atoms adjacent to the disulfide bond increases steric hindrance, enhancing stability in the blood. However, excessive steric hindrance can impede release. Optimal anti-tumor activity is typically achieved with moderate substitution [3].

Figure 4. Reductive cleavage of disulfide bond linkers [3]

Enzymatically Cleavable Linkers

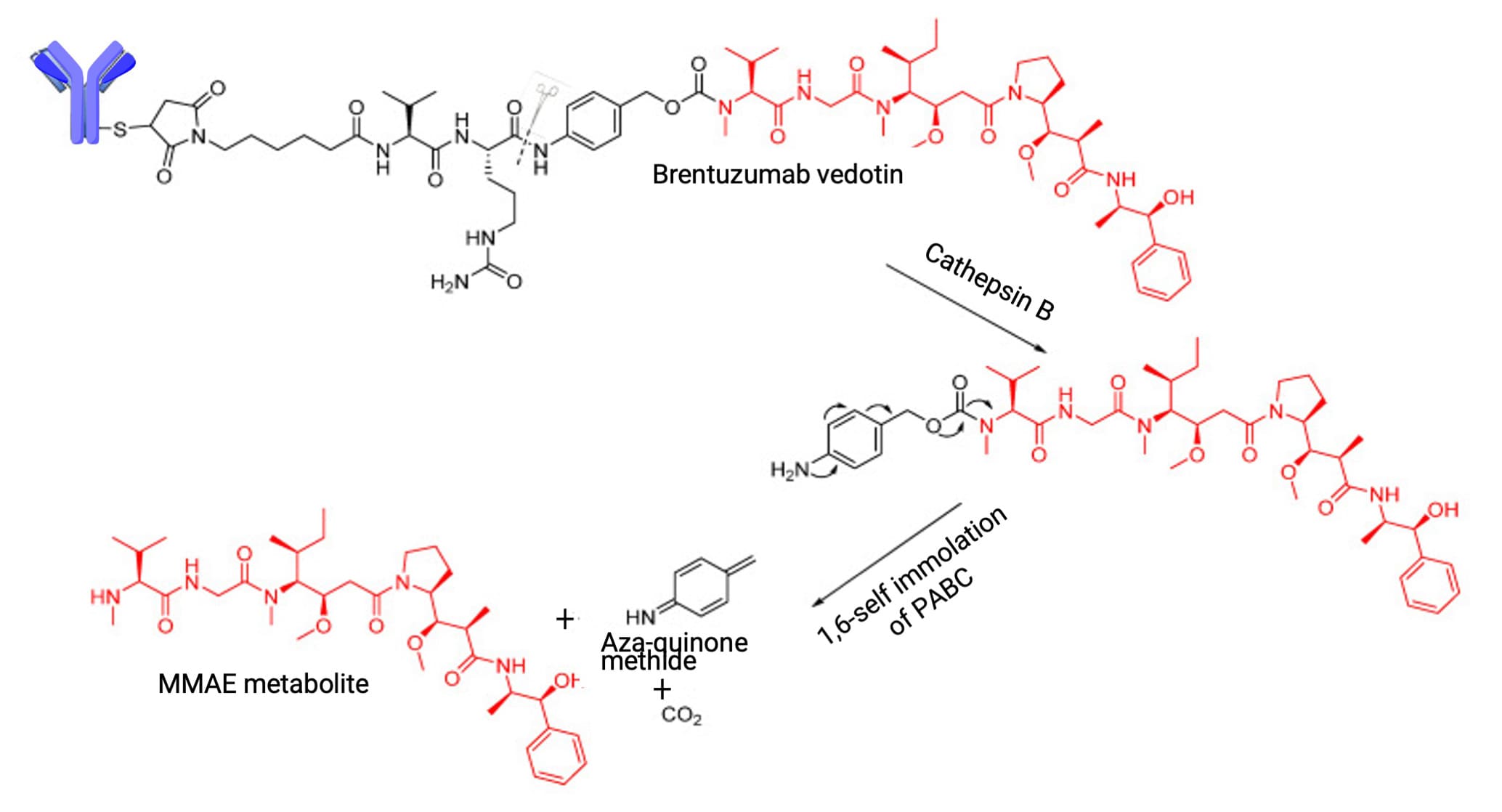

Unlike their chemical counterparts, enzymatically cleavable linkers leverage proteases that are highly expressed in tumor cells. Valine-Citrulline (VCit) is a prominent enzymatic unit in approved ADCs, designed for selective hydrolysis by lysosomal proteases at the amide bond between citrulline and the p-aminobenzyl carbamate (PABC) spacer (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Lysosomal protease cleavage of Valine-Citrulline (VCit) to release payload [4]

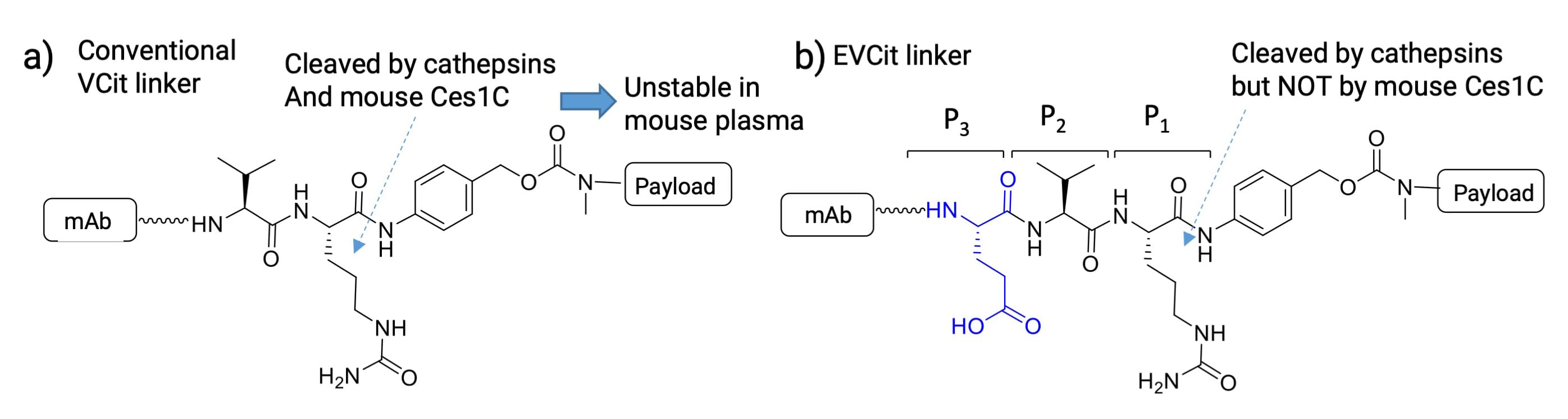

Despite its popularity, VCit exhibits species-dependent stability issues. While stable in human and monkey plasma, VCit-based ADCs show significantly reduced stability in mouse plasma due to hydrolysis by carboxylesterase 1c (Ces1c). This discrepancy complicates preclinical evaluation in murine models. To resolve this, researchers developed the Glutamic acid-Valine-Citrulline (EVCit) linker by adding an acidic amino acid at the N-terminus (Figure 6b) [5].

Comparative studies reveal that while both ADC linkers are cleaved by human cathepsin B (half-lives: VCit 4.6 h vs. EVCit 2.8 h), their stability in mouse plasma differs drastically. After 14 days, VCit-based ADCs lost over 95% of their payload, whereas EVCit analogs remained virtually intact. Thus, EVCit offers high sensitivity to cathepsins while resisting Ces1c-mediated hydrolysis, making it a robust option for ADC linker design.

Figure 6. a) VCit linker and b) EVCit linker structures [5]

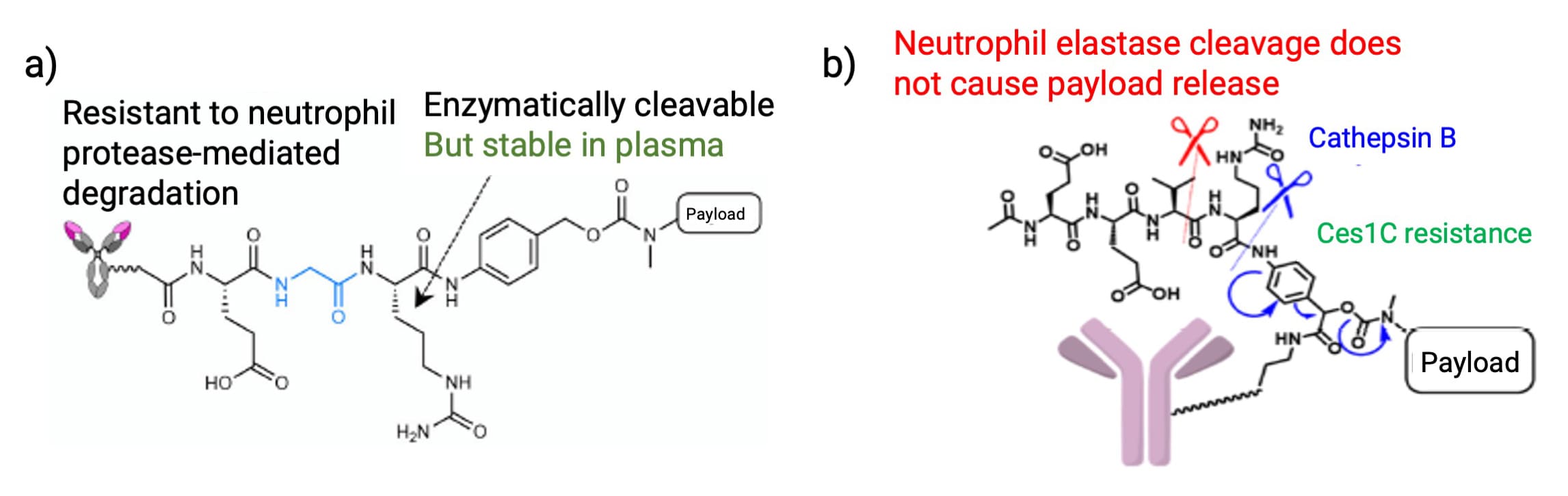

Additionally, VCit linkers are susceptible to cleavage by neutrophil elastase, which is implicated in clinical dose-limiting toxicities like neutropenia. Structural optimizations, such as replacing the P2 valine with glycine to form Glutamic acid-Glycine-Citrulline (EGCit) (Figure 7a) or designing a non-linear Exo-EEVCit linker (Figure 7b), have proven effective in resisting neutrophil elastase hydrolysis.

Figure 7. a) EGCit linker [6] and b) Exo-EEVCit linker structure [7]

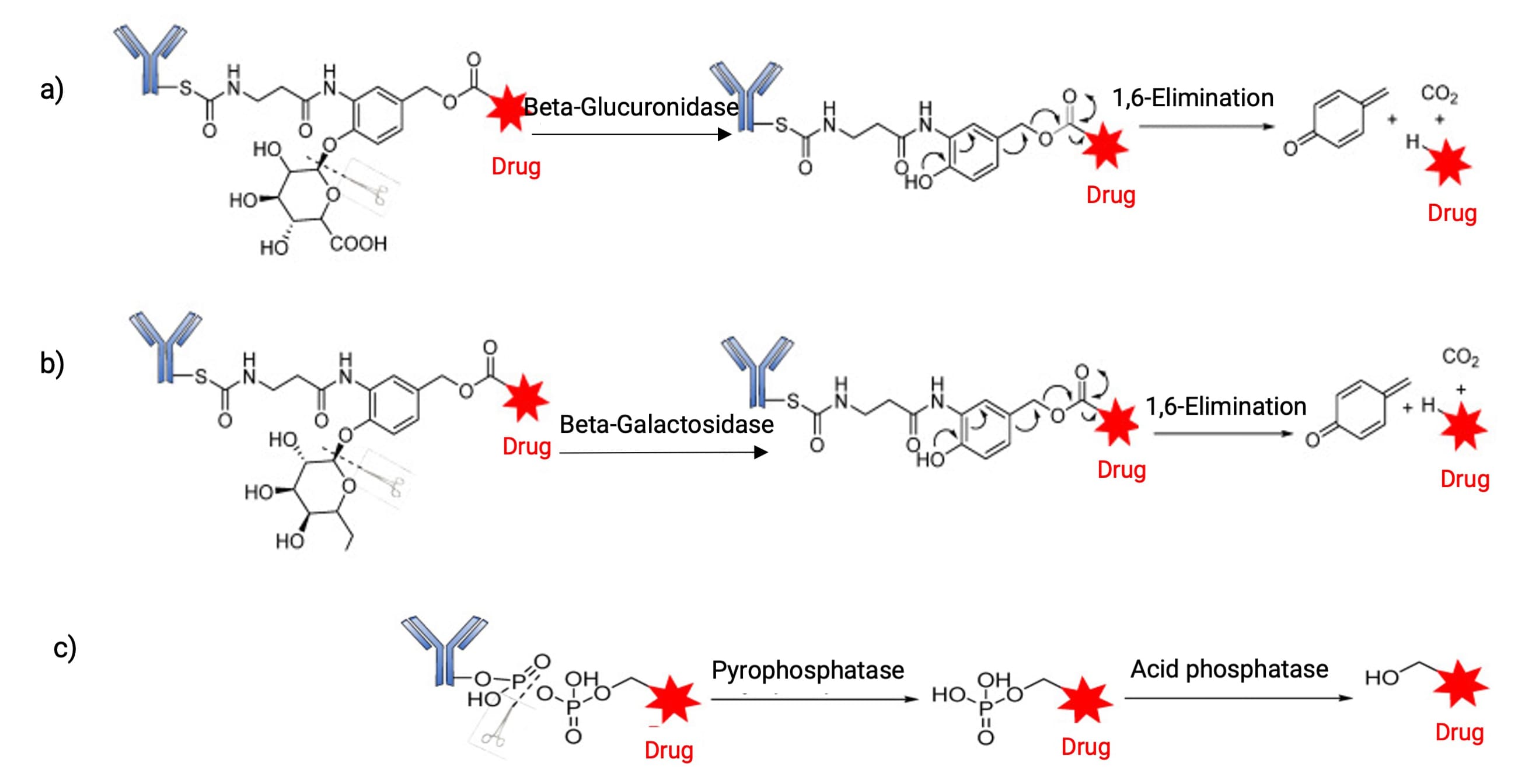

Beyond these examples, other protease-sensitive sequences (e.g., GGFG, VA, AA, AAN) and linkers responsive to different hydrolases (β-glucuronidase, β-galactosidase, phosphatase) are expanding the toolkit (Figure 8). These innovations aim to discover response units that maximize the therapeutic window by enhancing stability in circulation while ensuring efficient release in the tumor microenvironment.

Figure 8. Release mediated by a) β-glucuronidase, b) β-galactosidase, and c) phosphatase [4]

ADC Linker Conjugation Strategies: Functional Group Selection

The interface between the ADC linker and the antibody is critical. Design strategies here must balance conjugation stability with the uniformity of the drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR). Conjugation stability ensures safety, while a consistent DAR underpins reproducible pharmacokinetics and efficacy for ADCs.

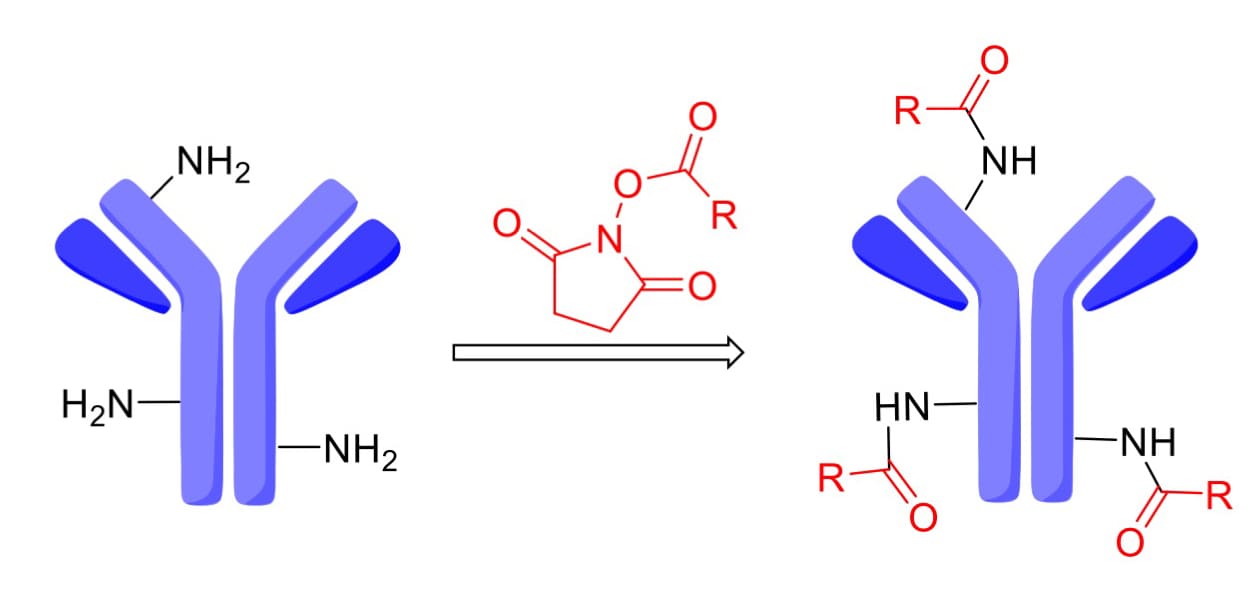

N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) Conjugation

Some ADCs utilize N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters to react with lysine (Lys) residues on the antibody, forming stable amide bonds (Figure 9). Since an IgG1 antibody carries approximately 90 surface Lys residues (with ~30 available for conjugation), this method can yield heterogeneous species with 1 to 30 payloads. However, controlled production conditions can achieve reproducible site occupancy distributions, supporting large-scale manufacturing despite the inherent heterogeneity.

Figure 9. Conjugation of N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) with lysine residues on an antibody [4]

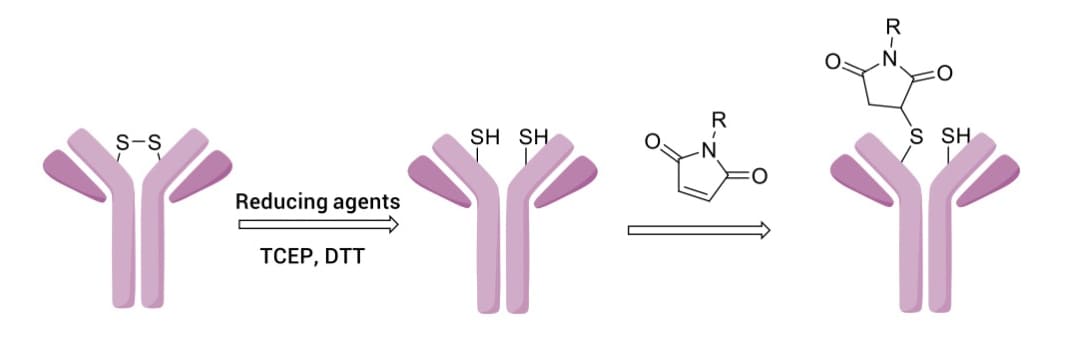

Maleimide Conjugation

Conjugation via maleimide (MC) reacting with cysteine (Cys) residues is a widely adopted strategy (Figure 10). By reducing interchain disulfide bonds with agents like TCEP or DTT, thiol groups are exposed to undergo Michael addition with maleimide. This approach targets 8 specific sites, significantly reducing DAR heterogeneity compared to lysine conjugation.

Figure 10. Maleimide conjugation with antibody interchain cysteine (generated by disulfide reduction) to produce thiosuccinimide [4]

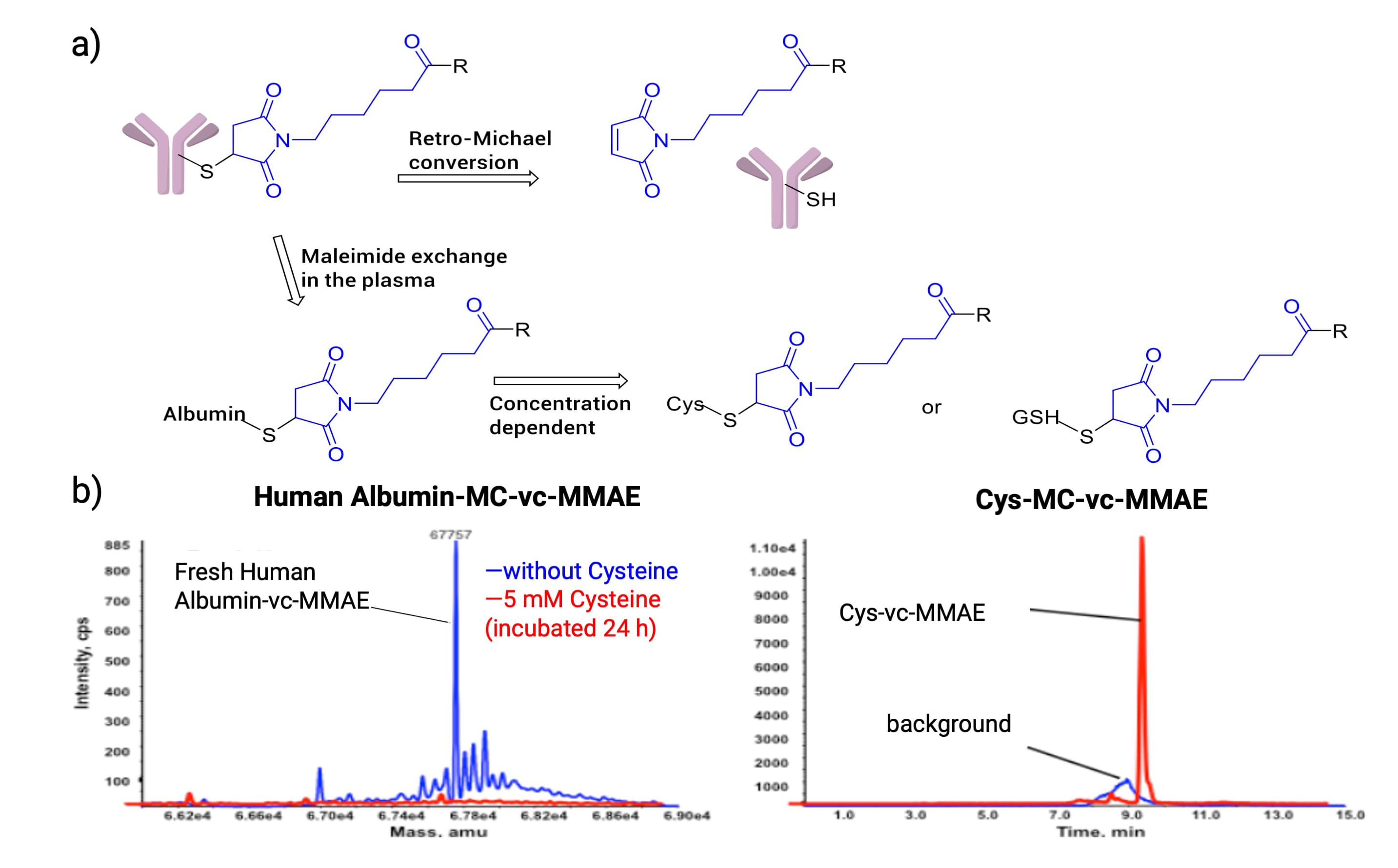

However, maleimide-conjugated ADCs face the risk of retro-Michael addition in circulation, causing premature payload loss. Research [8] indicates that the average DAR of a maleimide-ADC dropped from 8 to 3 after 168 hours in human plasma. The maleimide released via retro-Michael addition can rapidly covalently bind with plasma albumin, free cysteine, or glutathione, manifested as maleimide exchange (Figure 11a). Further experiments prove that the process of maleimide exchange is concentration-dependent. For instance, Albumin-MC-vc-MMAE fully converts to Cys-MC-vc-MMAE when incubated with excess cysteine (Figure 11b) [9].

Figure 11. (a) Maleimide-conjugated ADC undergoes retro-Michael addition and exchange with Albumin, Cys, or GSH; (b) Albumin-MC-vc-MMAE conversion to Cys-MC-vc-MMAE in human plasma [9]

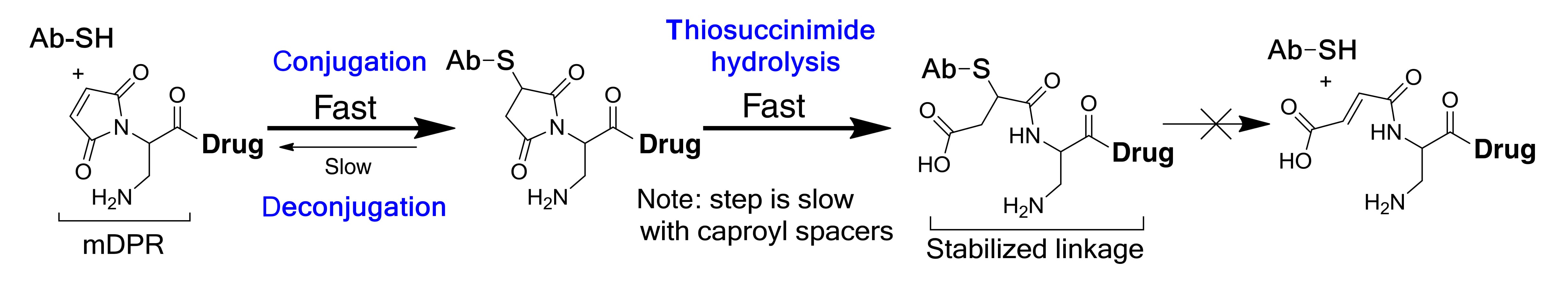

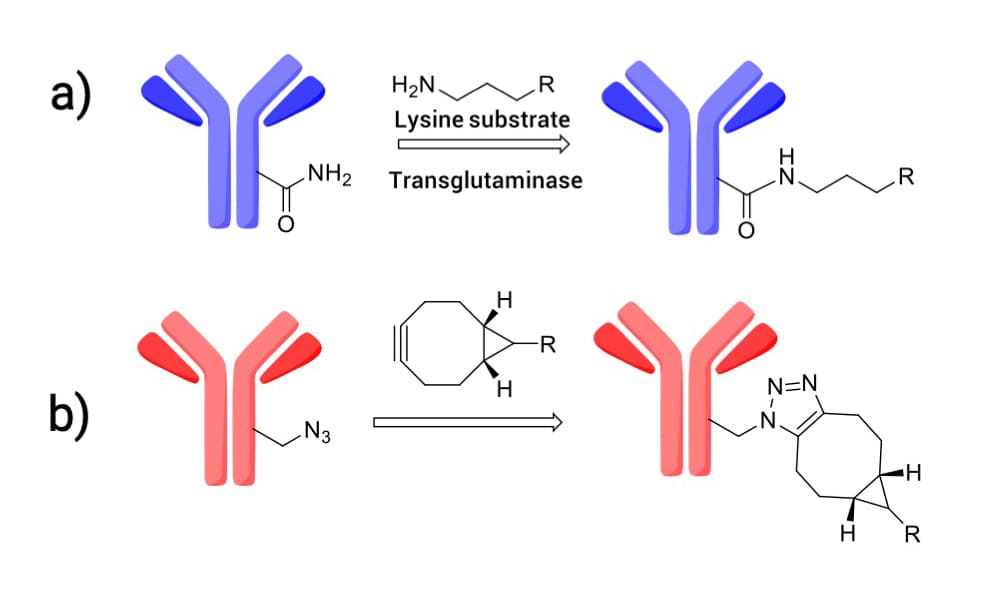

To mitigate this, researchers have leveraged the finding that ring-opening hydrolysis of the thiosuccinimide adduct stabilizes the linker-antibody bond. "Self-stabilizing maleimides" (mDPR) incorporate a basic amino group near the conjugation site to catalyze this ring-opening, locking the linker in place (Figure 12). Additionally, advanced techniques like enzymatic ligation (transglutaminase) and click chemistry are increasingly employed to create highly uniform and stable ADCs (Figure 13).

Figure 12. Ring-opening hydrolysis of self-stabilizing maleimide (mDPR) [10]

Figure 13. a) Transglutaminase-catalyzed conjugation; b) Click chemistry conjugation

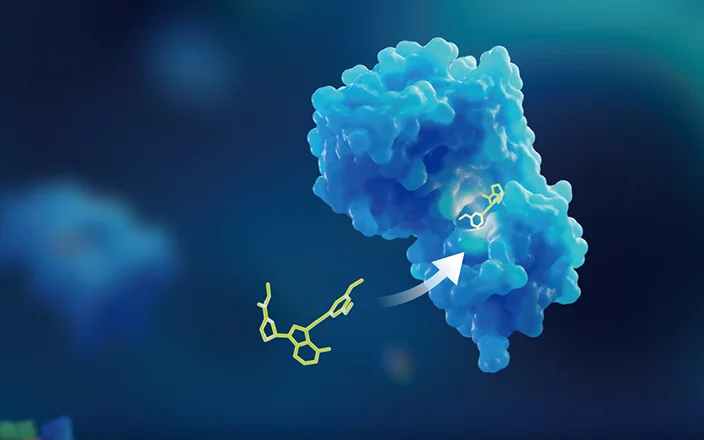

Self-Immolative Spacers in ADC Linker Design

Directly attaching an enzyme cleavage site to a cytotoxic payload can create steric hindrance that inhibits release. To address this, ADC linker design often incorporates self-immolative spacers.

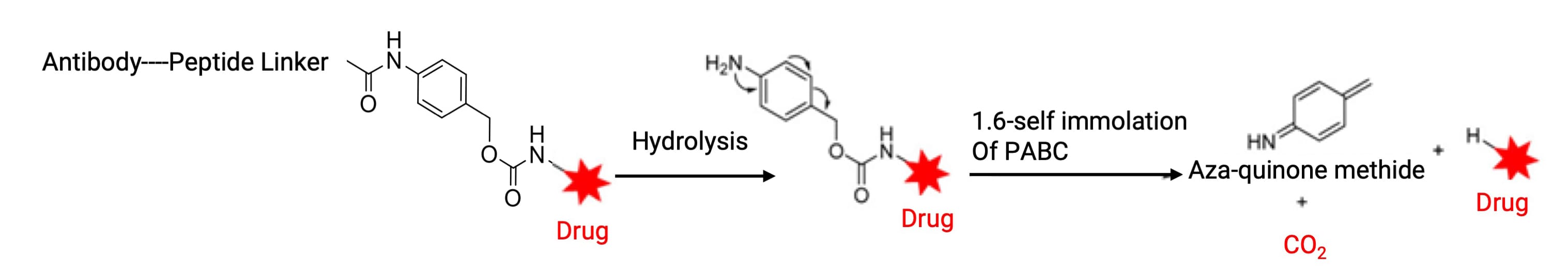

Para-aminobenzyl carbamate (PABC) is the most common self-immolative spacer (Figure 14). It serves a dual purpose: facilitating protease access to the cleavage site and spontaneously releasing the unmodified payload via 1,6-elimination after enzymatic activation.

Figure 14. Self-immolation of para-aminobenzyl carbamate (PABC) [4]

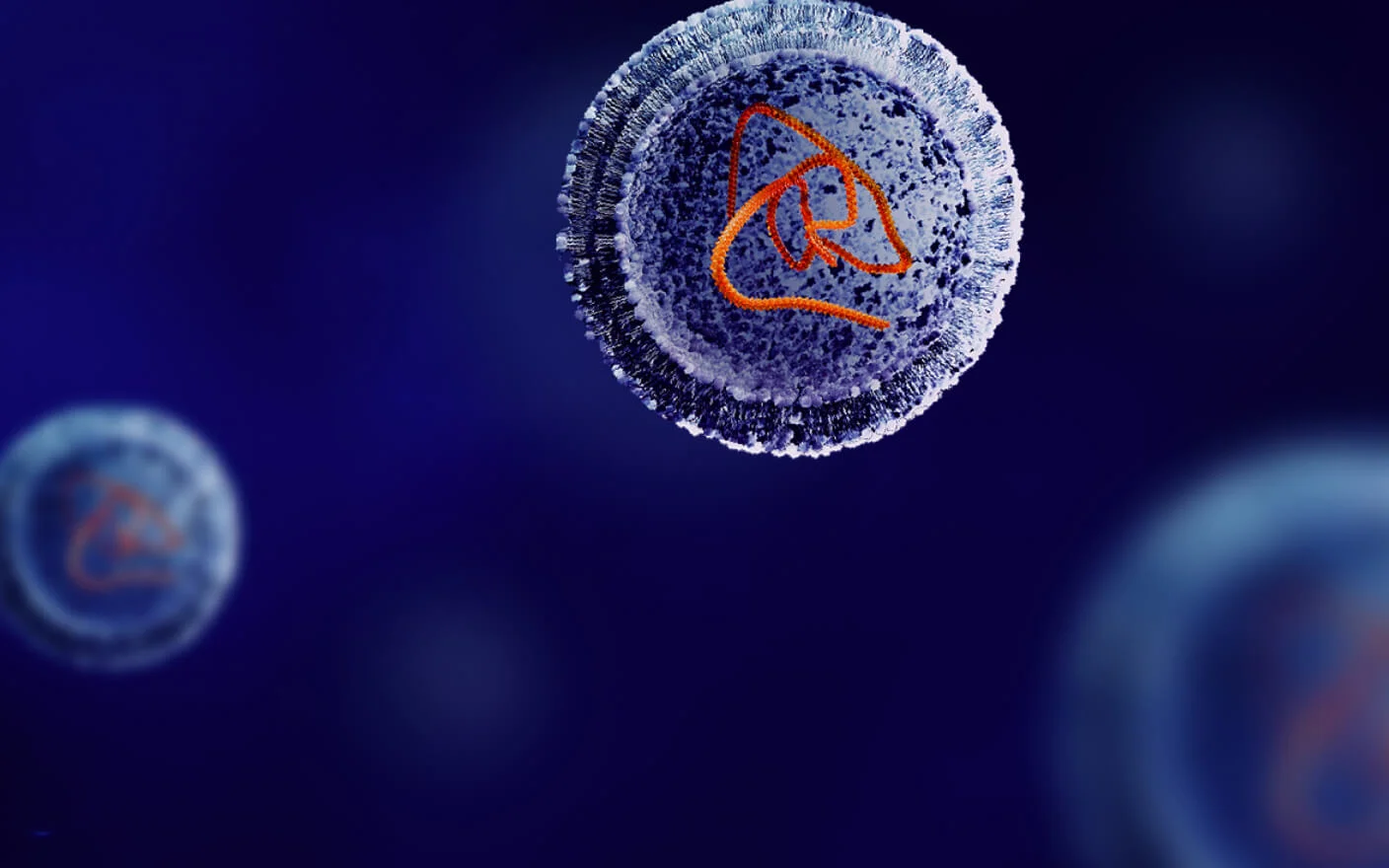

Since PABC requires a nitrogen attachment site on the payload, it is not universally applicable. For payloads with alcohol functional groups, the aminomethoxy (AM) spacer offers an effective alternative. Used in Trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu), the AM spacer undergoes self-immolation following the cleavage of the amide bond between the peptide linker (GGFG) and the spacer, releasing the free payload (DXd).

Hydrophilic Modification of ADC Linkers

Attaching hydrophobic payloads often increases the overall hydrophobicity of the ADC, leading to aggregation, faster clearance, and reduced efficacy. This issue is particularly acute for high-DAR constructs. A proven strategy to counteract this is the incorporation of hydrophilic groups within the linker.

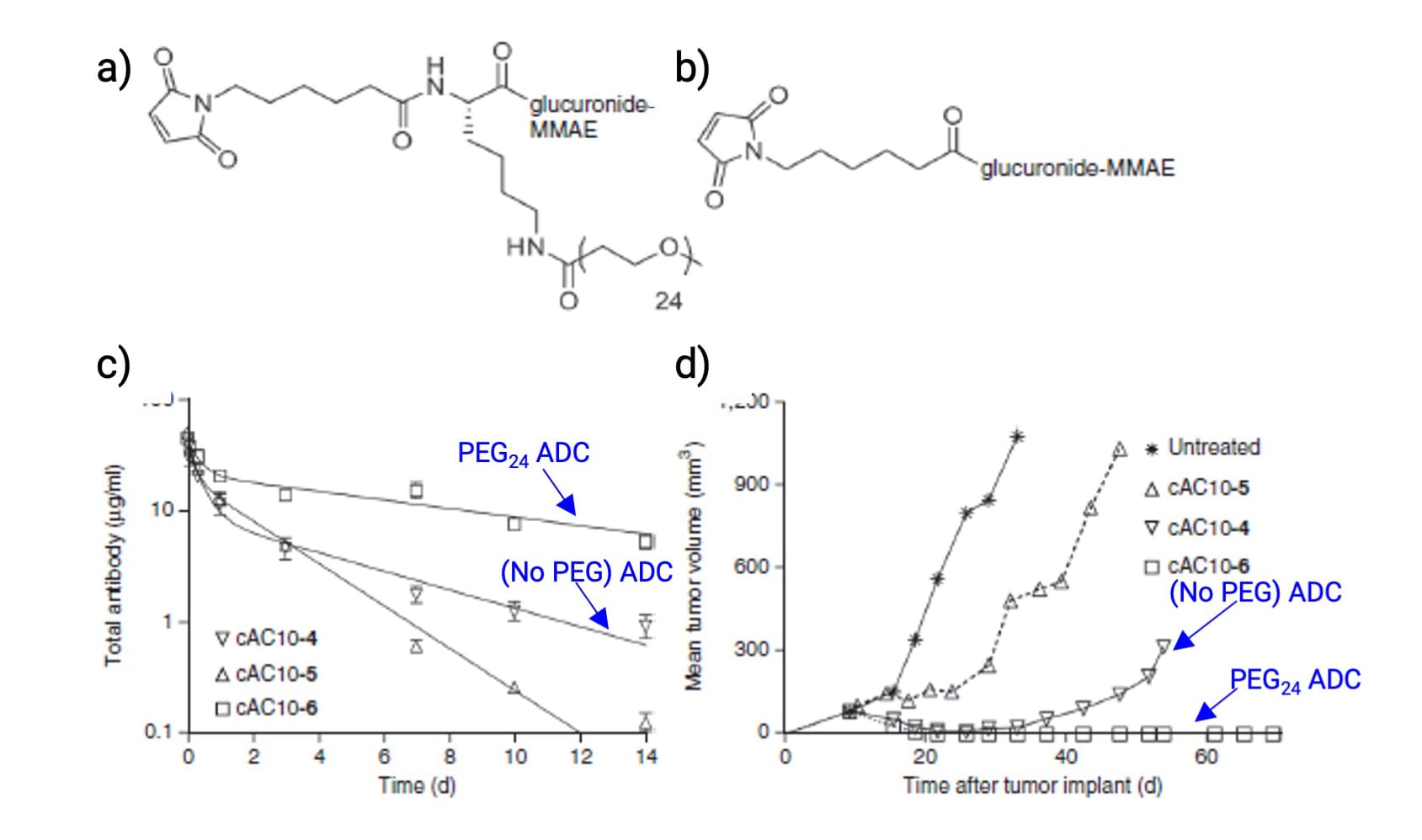

Figure 15. a) PEG24-branched ADC; b) Non-PEGylated ADC; c) Pharmacokinetics in rat plasma; d) Anti-tumor activity in mice [11]

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is frequently used (e.g., in Trodelvy and Zynlonta) to enhance solubility and stealth. ADCs with branched PEG chains (e.g., PEG24) demonstrate lower hydrophobicity, extended circulation time, and superior anti-tumor activity compared to non-PEGylated variants (Figure 15).

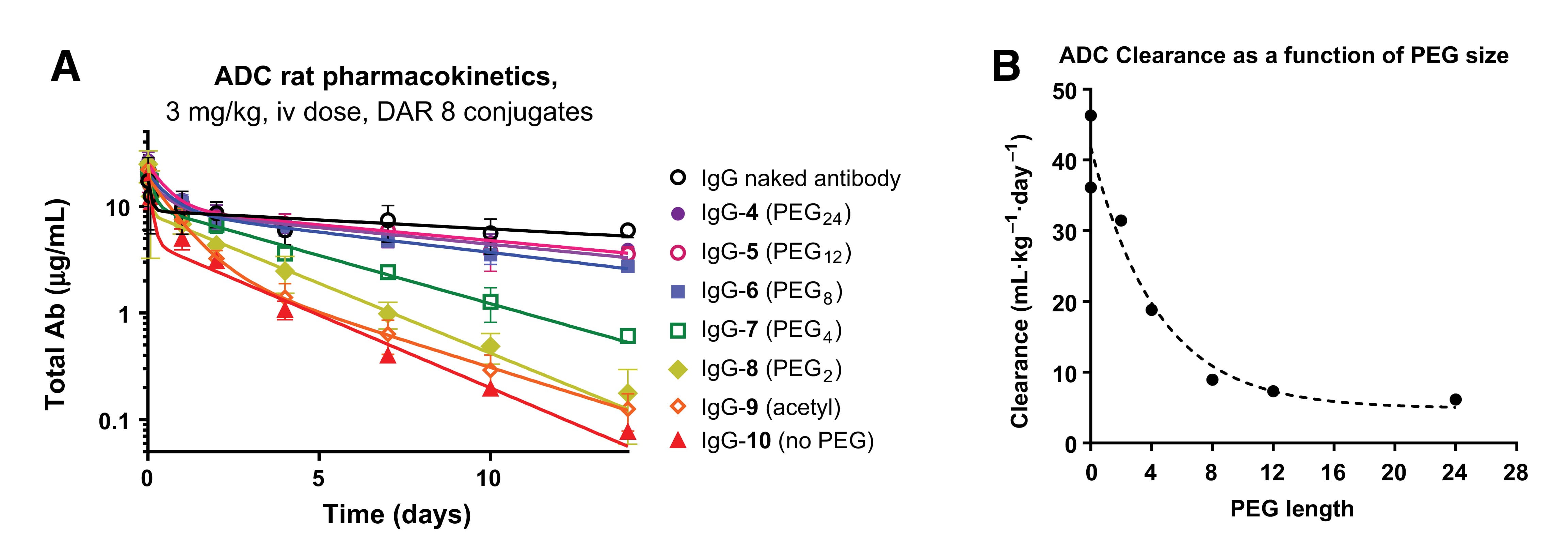

Interestingly, the length of the PEG chain dictates pharmacokinetic outcomes. Plasma exposure increases with chain length up to PEG8, where it plateaus near the levels of the naked antibody. Shorter chains or the absence of PEG result in significantly faster clearance (Figure 16). Beyond PEG, other hydrophilic moieties like cyclodextrins and polysarcosine are emerging as effective tools for modifying ADC linkers.

Figure 16. Effect of PEG chain length on ADC pharmacokinetics [10]

In Vitro DMPK Evaluation for ADC Linker Stability

An ideal ADC linker must maintain high stability in circulation while ensuring release at the target. In vitro DMPK assessments are essential for verifying these properties.

Plasma and whole blood stability: Incubating linker-payloads or ADCs in plasma or whole blood allows for the quantification of premature cleavage. This helps identify instability issues early in the design process.

Target cell release: While plasma models assess stability, target cell models (e.g., tumor cells) assess efficacy. Co-incubation of ADCs with target cells validates the linker's ability to release the payload intracellularly.

Surrogate models (Lysosome/S9): Due to the low throughput of cell models, lysosomal fractions and liver S9 fractions serve as high-throughput surrogates for screening novel linkers (Table 2).

Table 2. Core In Vitro DMPK Evaluation Systems

Study System | Detection Target | Characteristics |

Plasma / Whole Blood | Payload detection, metabolite ID, DAR analysis | Contains hydrolases. Assesses circulatory stability. High throughput. |

Lysosome / S9 | Payload release, metabolite ID | High enzyme concentration. Assesses cleavage efficiency. High throughput. |

Tumor Cells | Payload release, metabolite ID | Broad enzyme profile. Direct efficacy assessment. Low throughput. |

Critical Considerations:

Analysis target: For novel linkers, actual cleavage sites may differ from theoretical designs. Free payload detection was needed, and additional attention to "linker fragment-payload", payload secondary metabolites, "amino acid residue-linker-payload", and de-conjugation byproducts was recommended in linker‑payloads or ADCs incubation.

Maleimide management: For linker-payloads containing free maleimide, blocking with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is crucial to prevent inhibition of cysteine proteases during assays. As for maleimide-conjugated ADC, maleimide exchange with albumin cannot be detected by simple small-molecule assays, and thus DAR distribution detection was necessary to evaluate the in vitro stability.

Totally, stability evaluation requires a combination of payload detection, metabolite identification, and DAR analysis to provide a complete picture of the ADC linker's integrity.

Final Words

The fusion of antibody precision with small-molecule potency places ADCs at the forefront of oncology. The ADC linker—whether a cleavable linker or a non-cleavable linker—is the critical determinant of the drug's therapeutic index. While significant progress has been made in ADC linker design to reduce off-target toxicity and enhance stability, no single strategy fits every scenario. Success requires a tailored approach, balancing antibody behavior, payload properties, and biological targets.

WuXi AppTec DMPK offers a comprehensive platform for ADC evaluations, integrating in vitro stability (plasma/blood), payload release (lysosome/S9/cell models), and in vivo pharmacokinetics. By providing rigorous data on payload release, metabolite profiles, and DAR evolution, we empower developers to optimize their ADC linker designs for clinical success.

Authors: Huijuan Wang, Ruixing Li, Weiqun Cao, Liqi Shi, Qigan Cheng

Talk to a WuXi AppTec expert today to get the support you need to achieve your drug development goals.

Committed to accelerating drug discovery and development, we offer a full range of discovery screening, preclinical development, clinical drug metabolism, and pharmacokinetic (DMPK) platforms and services. With research facilities in the United States (New Jersey) and China (Shanghai, Suzhou, Nanjing, and Nantong), 1,000+ scientists, and over fifteen years of experience in Investigational New Drug (IND) application, our DMPK team at WuXi AppTec are serving 1,600+ global clients, and have successfully supported 1,700+ IND applications.

Reference

[1] Su Z, Xiao D, Xie F, et al. Antibody–drug conjugates: Recent advances in linker chemistry[J]. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B, 2021, 11(12): 3889-3907.

[2] Yang L, Ma J, Liu B, et al. Recent Advances in Peptide Linkers of Antibody–Drug Conjugates[J]. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2025, 68(17): 18099-18113.

[3] Bargh J D, Isidro-Llobet A, Parker J S, et al. Cleavable linkers in antibody–drug conjugates[J]. Chemical Society Reviews, 2019, 48(16): 4361-4374.

[4] Sheyi R, de la Torre BG, Albericio F. Linkers: An Assurance for Controlled Delivery of Antibody-Drug Conjugate. Pharmaceutics. 2022; 14(2):396.

[5] Anami Y, Yamazaki C M, Xiong W, et al. Glutamic acid–valine–citrulline linkers ensure stability and efficacy of antibody–drug conjugates in mice[J]. Nature communications, 2018, 9(1): 2512.

[6] Ha S Y Y, Anami Y, Yamazaki C M, et al. An enzymatically cleavable tripeptide linker for maximizing the therapeutic index of antibody–drug conjugates[J]. Molecular cancer therapeutics, 2022, 21(9): 1449-1461.

[7] Watanabe T, Fujii T, Matsuda Y. Exo-Cleavable Linkers: Enhancing Stability and Therapeutic Efficacy in Antibody-Drug Conjugates[J]. Journal of Synthetic Organic Chemistry, Japan, 2024, 82(11): 1117-1124.

[8] Li Z, Zhang J, Wu Y, et al. Integrated strategy for biotransformation of antibody drug conjugates and multidimensional interpretation via high-resolution mass spectrometry[J]. Drug Metabolism and Disposition, 2025: 100081.

[9] Shen B Q, Xu K, Liu L, et al. Conjugation site modulates the in vivo stability and therapeutic activity of antibody-drug conjugates[J]. Nature biotechnology, 2012, 30(2): 184-189.

[10] Burke P J, Hamilton J Z, Jeffrey S C, et al. Optimization of a PEGylated glucuronide-monomethylauristatin E linker for antibody–drug conjugates[J]. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 2017, 16(1): 116-123.

[11] Lyon R P, Bovee T D, Doronina S O, et al. Reducing hydrophobicity of homogeneous antibody-drug conjugates improves pharmacokinetics and therapeutic index[J]. Nature biotechnology, 2015, 33(7): 733-735.

Related Services and Platforms

-

MetID (Metabolite Profiling and Identification)Learn More

MetID (Metabolite Profiling and Identification)Learn More -

Novel Drug Modalities DMPK Enabling PlatformsLearn More

Novel Drug Modalities DMPK Enabling PlatformsLearn More -

In Vitro MetID (Metabolite Profiling and Identification)Learn More

In Vitro MetID (Metabolite Profiling and Identification)Learn More -

In Vivo MetID (Metabolite Profiling and Identification)Learn More

In Vivo MetID (Metabolite Profiling and Identification)Learn More -

Metabolite Biosynthesis and Structural CharacterizationLearn More

Metabolite Biosynthesis and Structural CharacterizationLearn More -

Metabolites in Safety Testing (MIST)Learn More

Metabolites in Safety Testing (MIST)Learn More -

PROTAC DMPK ServicesLearn More

PROTAC DMPK ServicesLearn More -

ADC DMPK ServicesLearn More

ADC DMPK ServicesLearn More -

Oligo DMPK ServicesLearn More

Oligo DMPK ServicesLearn More -

PDC DMPK ServicesLearn More

PDC DMPK ServicesLearn More -

Peptide DMPK ServicesLearn More

Peptide DMPK ServicesLearn More -

mRNA DMPK ServicesLearn More

mRNA DMPK ServicesLearn More -

Covalent Drugs DMPK ServicesLearn More

Covalent Drugs DMPK ServicesLearn More

Stay Connected

Keep up with the latest news and insights.