Research into the lymphatic system plays a vital role in developing drugs that treat lymphatic diseases and utilizing the lymphatic pathway to enhance drug absorption [1]. A key advantage of lymphatic drug delivery is the direct transport of drugs to the immune system, effectively bypassing hepatic first-pass metabolism.

In recent years, an increasing number of biological targets within the lymphatic system have been identified and utilized. Consequently, the absorption, distribution, transport, and metabolic processes of drugs via lymphatic circulation, along with related delivery systems, have garnered widespread attention. This article elucidates the mechanisms of the lymphatic pathway and transport, and discusses both in vitro and in vivo research models, with a specific focus on the establishment and application of the rat lymphatic cannulation model.

Understanding the Lymphatic Pathways and Circulation Mechanisms

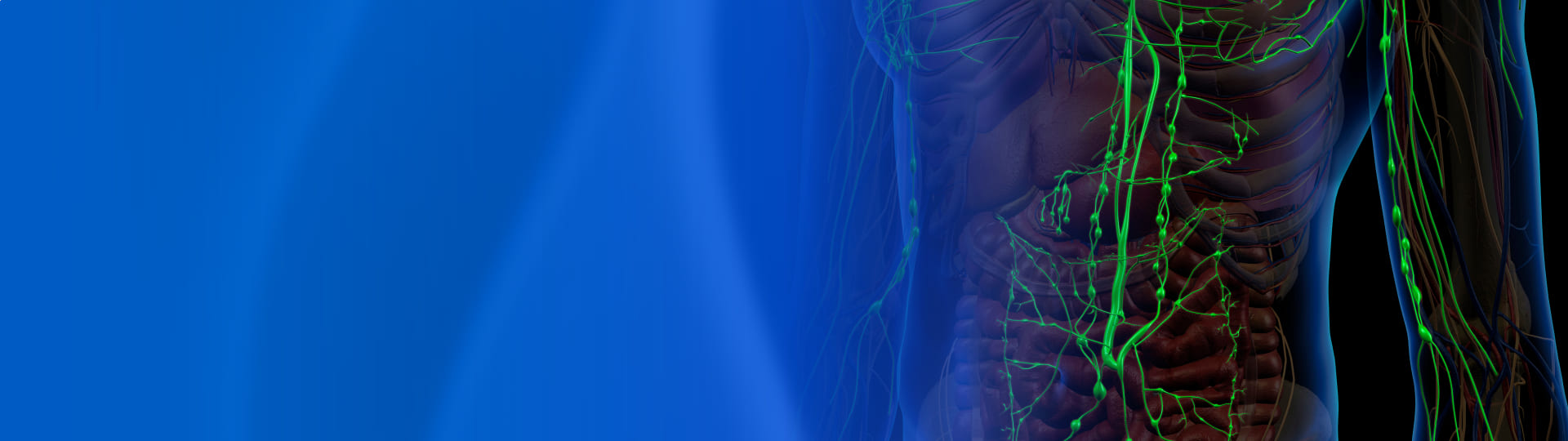

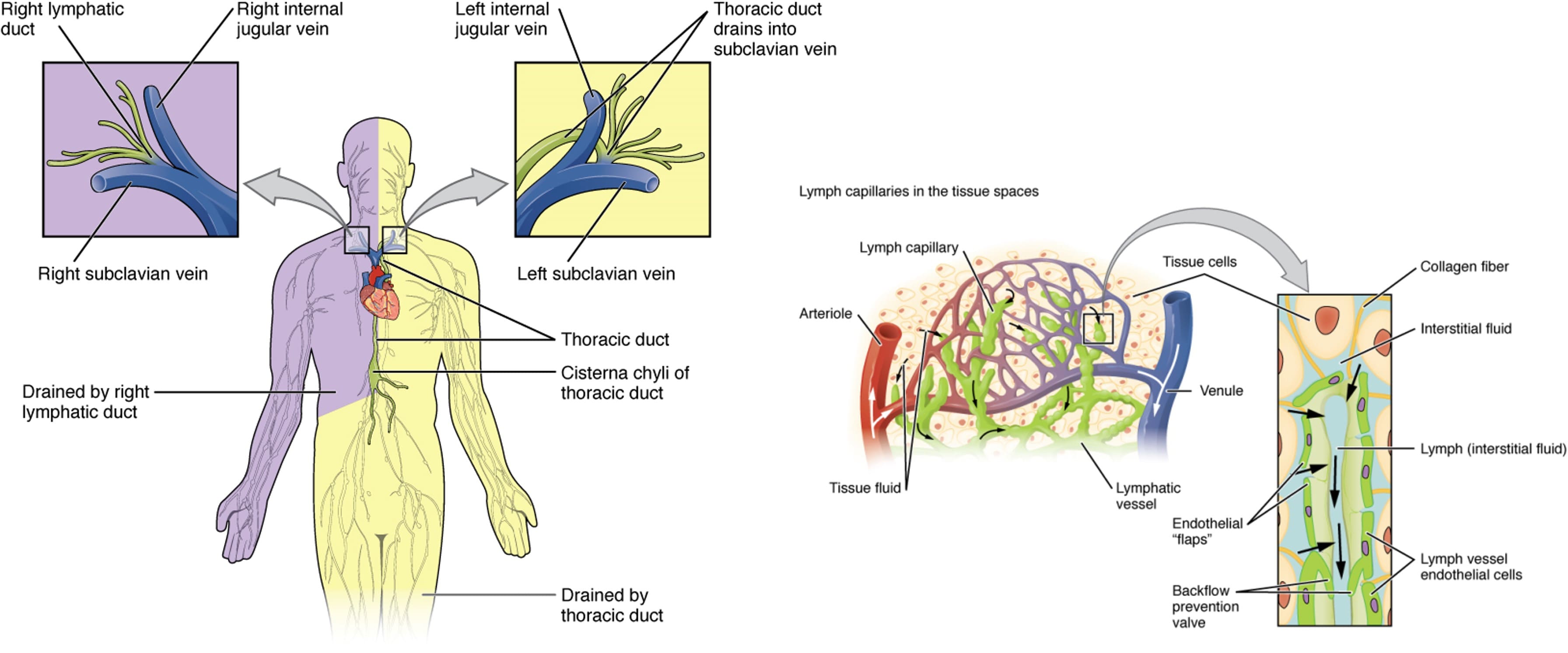

The lymphatic system is a crucial component of the human immune defense system. It is primarily composed of lymphatic vessels (such as lymphatic capillaries, trunks, and ducts), lymphoid tissues (such as diffuse lymphoid tissue and lymph nodes), and lymphoid organs (such as the thymus, bone marrow, and tonsils) (see Figure 1) [2].

The human lymphatic network intertwines with the vascular network, and together they form the circulatory system. Unlike the vascular system, the lymphatic system is an open-loop circuit. Tissue fluid enters vessels through lymphatic drainage pathways starting at the capillaries. These capillaries flow into larger pre-collecting vessels and then into lymph nodes. Finally, the vessels converge at the thoracic duct (cisterna chyli) or the right lymphatic duct, draining lymph into the blood circulation at the subclavian vein. Therefore, the lymphatic system performs essential physiological functions, including maintaining fluid balance, clearing cellular debris and toxic waste, regulating immunity, and transporting lipids (in the form of albumin) from tissues to the blood circulation [3, 4].

Figure 1. Main trunk and ducts of the lymphatic system with local magnification of interstitial lymphatic capillaries [5]

Mechanisms of Lymphatic Transport and Drug Absorption

Capillaries and lymphatic vessels possess distinct physiological structures, resulting in significant differences in the lymphatic transport of large versus small molecule drugs.

Small-molecule drugs: Can be freely absorbed by both blood and lymphatic vessels. However, blood flow is 100–500 times greater than lymph flow, creating "sink conditions" in the blood. Thus, small-molecule drugs are primarily absorbed via the blood [6, 7].

Macromolecular drugs: Compounds (molecular weight >20 kDa or diameter 10–100 nm) are too large for capillary endothelium, making them more suitable for absorption via the lymphatic pathway. Highly lipophilic drugs bind to lipoproteins and enter systemic circulation via mesenteric lymph vessels, avoiding the hepatic first-pass effect.

Researchers are also utilizing macromolecules as carriers to facilitate the entry of small-molecule drugs into the lymphatic transport system, increasing drug release at target sites and enhancing systemic exposure.

Advantages of intestinal lymphatic transport compared to portal vein absorption include:

Avoidance of First-Pass Metabolism: Intestinal lymphatic transport effectively bypasses the liver [8].

Modulation via Formulation: Adjustments to formulation can influence the transport and PK parameters of highly lipophilic compounds, aiding in therapeutic and toxicological evaluations [9].

Targeted Efficacy: As the lymphatic system is the primary channel for T and B lymphocytes and tumor metastasis, this pathway can improve the efficacy of lymph-targeting drugs [10].

In Vitro and In Vivo Models for Lymphatic Transport Research

In Vitro Caco-2 Cell Models

The Caco-2 cell model is widely used for studying lymphatic transport in vitro. Because these cells can secrete triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs) and facilitate mechanistic studies at the cellular level, they are used to evaluate intestinal lymphatic transport and the impact of lipids and excipients on drug-lipoprotein binding. This makes them an effective tool for identifying candidates for intestinal lymphatic transport [11].

For example, Seeballuck et al. [12] used the Caco-2 model to study the effects of surfactants Polysorbate 60 and Polysorbate 80 on lipoprotein secretion in the small intestine. The study showed that Caco-2 cells digested Polysorbate 80 to release oleic acid, which the cells used to promote the basolateral secretion of TRLs (including chylomicrons). Polysorbate 80 elicited a similar response in an in vivo rat model, stimulating increased triglyceride secretion in mesenteric lymph, whereas Polysorbate 60 did not trigger a similar reaction.

In Vivo Rat Lymphatic Cannulation Models

Evaluating drug transport within the lymphatic system in vivo has always been a research challenge. Assessing lymphatic transport requires lymphatic cannulation to directly measure drug concentration in the lymph. However, because lymphatic cannulation is an irreversible surgery, these studies cannot be performed in humans. Consequently, researchers have established various animal models to quantitatively describe lymphatic drug transport.

These animal models involve collecting lymph flowing into the mesenteric or thoracic lymph ducts. The amount of drug transported is calculated by multiplying the lymph volume collected over time by the drug concentration. In 1948, Bollman et al. established the first rat mesenteric lymph drainage technique [13], facilitating many subsequent studies. However, this surgery is difficult, has a low success rate, and requires the animal to be anesthetized or restrained, which prevents the simulation of lymphatic transport under normal physiological conditions.

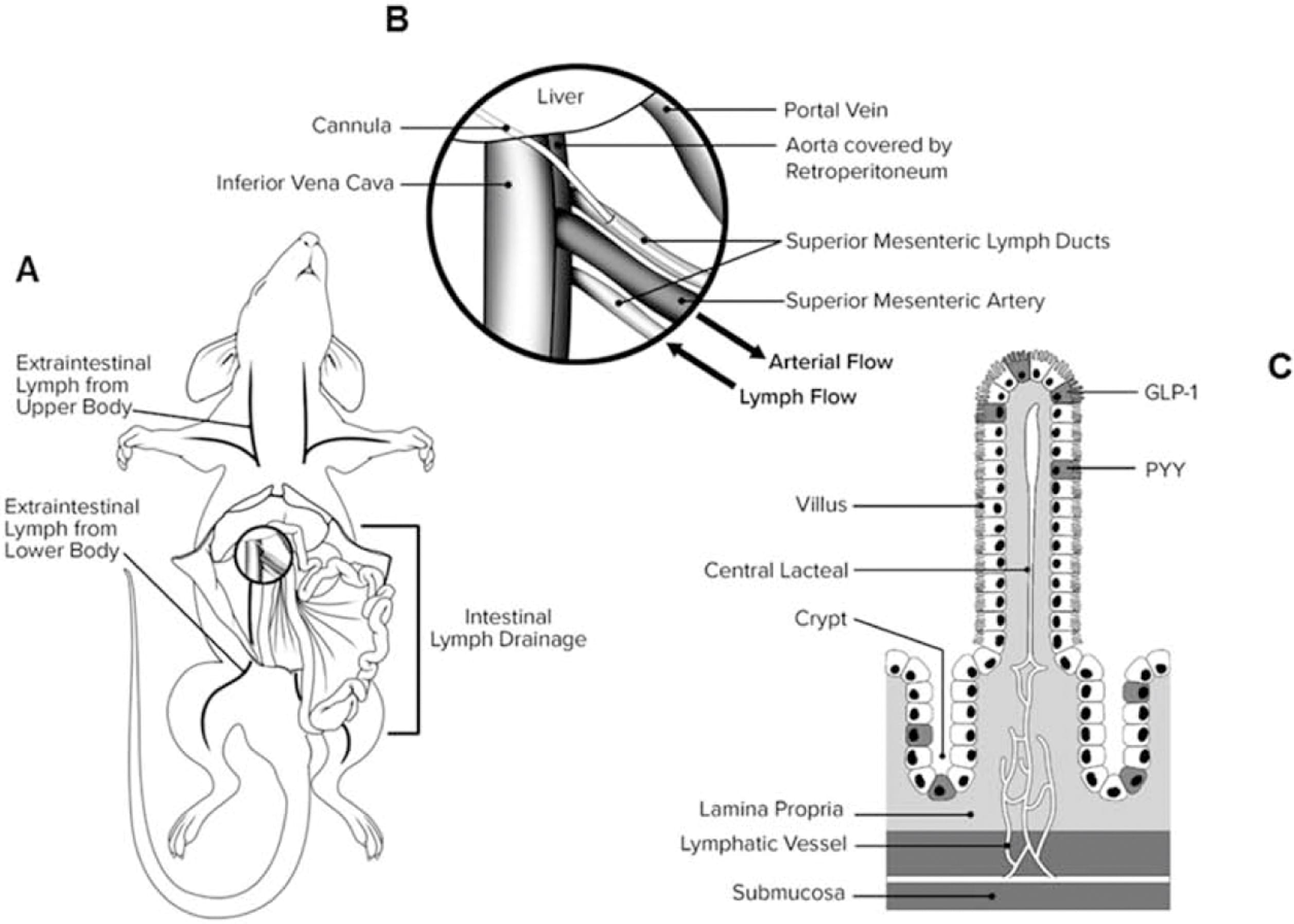

Currently, the rat lymphatic cannulation model is one of the most commonly used models (see Figure 2). Both anesthetized and conscious rat models have specific advantages and disadvantages, as outlined in Table 1.

Figure 2. Diagram of rat mesenteric lymph duct cannulation model [14]

Table 1. Comparison of anesthetized vs. conscious rat lymphatic transport models

Animal Model | Administration | Surgery Type | Duration | Pros and Cons |

Anesthetized | Duodenal | Mesenteric lymph duct / Thoracic duct cannulation | ≤ 8 hours | • Animal movement is restricted. • Bypasses gastric digestion. • Drainage tube is less likely to block after cannulation. |

Conscious* | Oral | Mesenteric lymph duct / Thoracic duct cannulation | ≤ 6 days | • Animal moves freely. • Drug undergoes a complete digestive process. • Avoids the physiological impact of anesthesia. • Risk of drainage tube blockage due to animal activity. |

*Freely moving rats

Case Study: WuXi AppTec DMPK Lymphatic Transport Model Validation

WuXi AppTec DMPK has established related rat lymphatic transport/absorption models. Using Vitamin D3 and Halofantrine Hydrochloride (highly lipophilic compounds) as test drugs [15-19], we evaluated the impact of anesthesia on lymphatic transport and how different lymph collection sites affect related PK research. The experimental design is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Experimental design for validation of anesthetized and non-anesthetized rat lymphatic transport models

Exp. Class | Group | Strain | Anesthesia (Y/N) | Route | Test Drug | Surgery Type | Sample Collection | |

Blood (Y/N) | Lymph (Y/N) | |||||||

A | 1 | SD Rat/Male | Y | Duodenal | Vitamin D3 | Mesenteric Cannulation | N | Y |

2 | SD Rat/Male | N | Oral | N | Y | |||

B | 3 | SD Rat/Male | N | Oral | Halofantrine HCl | Thoracic Duct | Y | Y |

4 | SD Rat/Male | N | Oral | Mesenteric Cannulation | Y | Y | ||

5 | SD Rat/Male | N | Oral | Portal Vein Cannulation | Y | N | ||

6 | SD Rat/Male | N | Oral | Non-surgical | Y | N | ||

Table 3. Relevant PK parameters of Vitamin D3 in lymph fluid under anesthetized and conscious animal models [15]

Total Drug Recovery in Lymph (% / 8h) | Lymph Flow Rate (µL / 8h) | AUC0-8h in Plasma of Sham Group (µg·h / mL)** | |

Anesthetized | 9 ± 1.5 | 2461.2 ± 1028.4 | 4.8 ± 0.7 |

Conscious | 12 ± 1.8 | 7366.6 ± 1501.9 | 6.5 ± 0.9 |

**Mesenteric lymph duct sham surgery: Anesthetized animals underwent laparotomy to expose the mesenteric lymph duct, followed by 30 minutes of stasis.

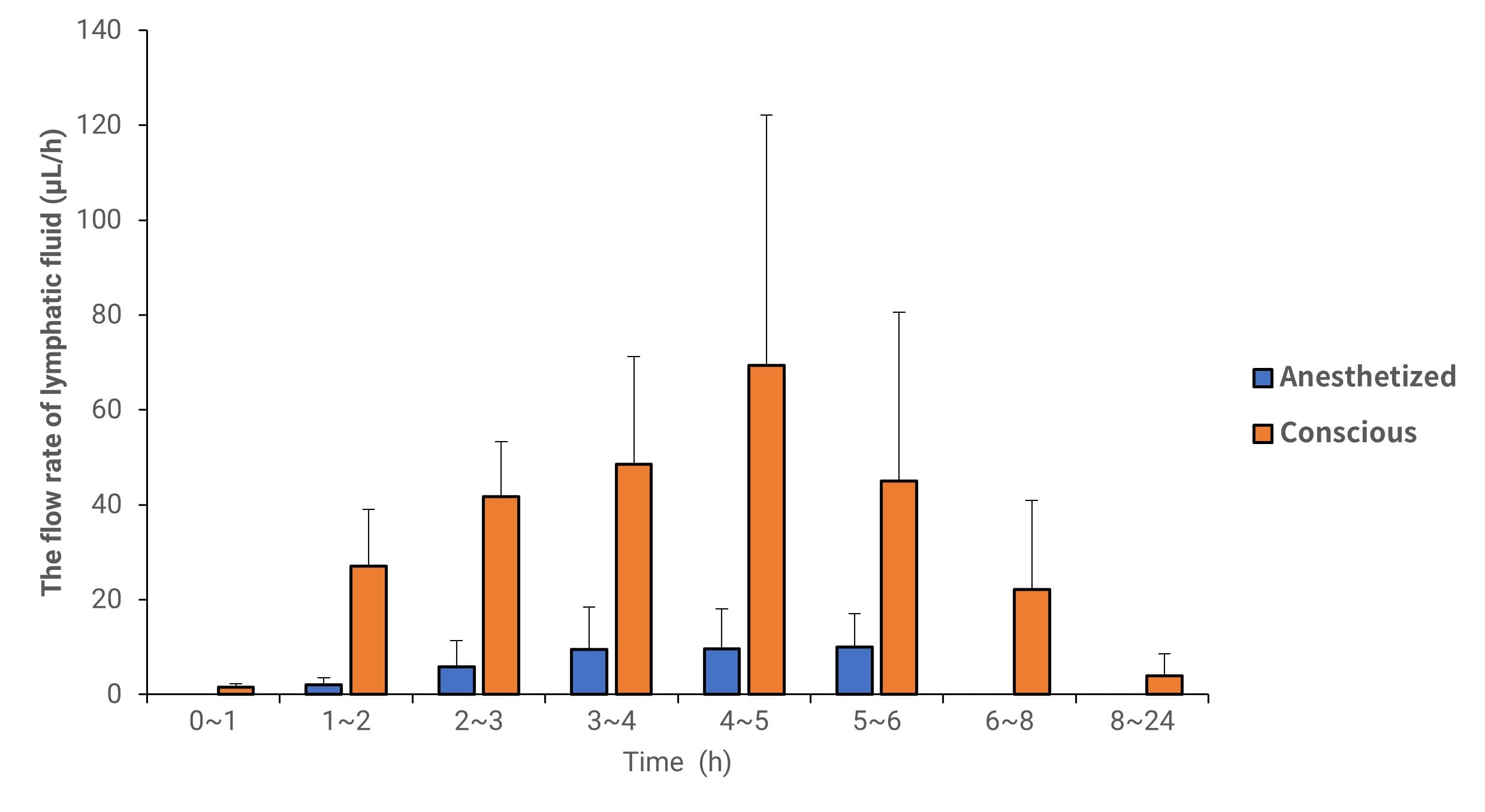

Figure 3. Lymph flow rate of Vitamin D3 in anesthetized and conscious lymphatic transport animal models (Data expressed as Mean ± SD, n=4)

Table 4. Relevant PK parameters of Vitamin D3 in lymph fluid under anesthetized and conscious animal models

Total Drug Recovery (µg) | Total Recovery Rate in Lymph (%/6h) | Lymph Flow Rate (µL/6h) | |

Anesthetized | 37.1 ± 31.0 | 3.20 ± 2.1 | 3597 ± 1564 |

Conscious | 341 ± 179 | 13.0 ± 3.3 | 12644 ± 4.85 |

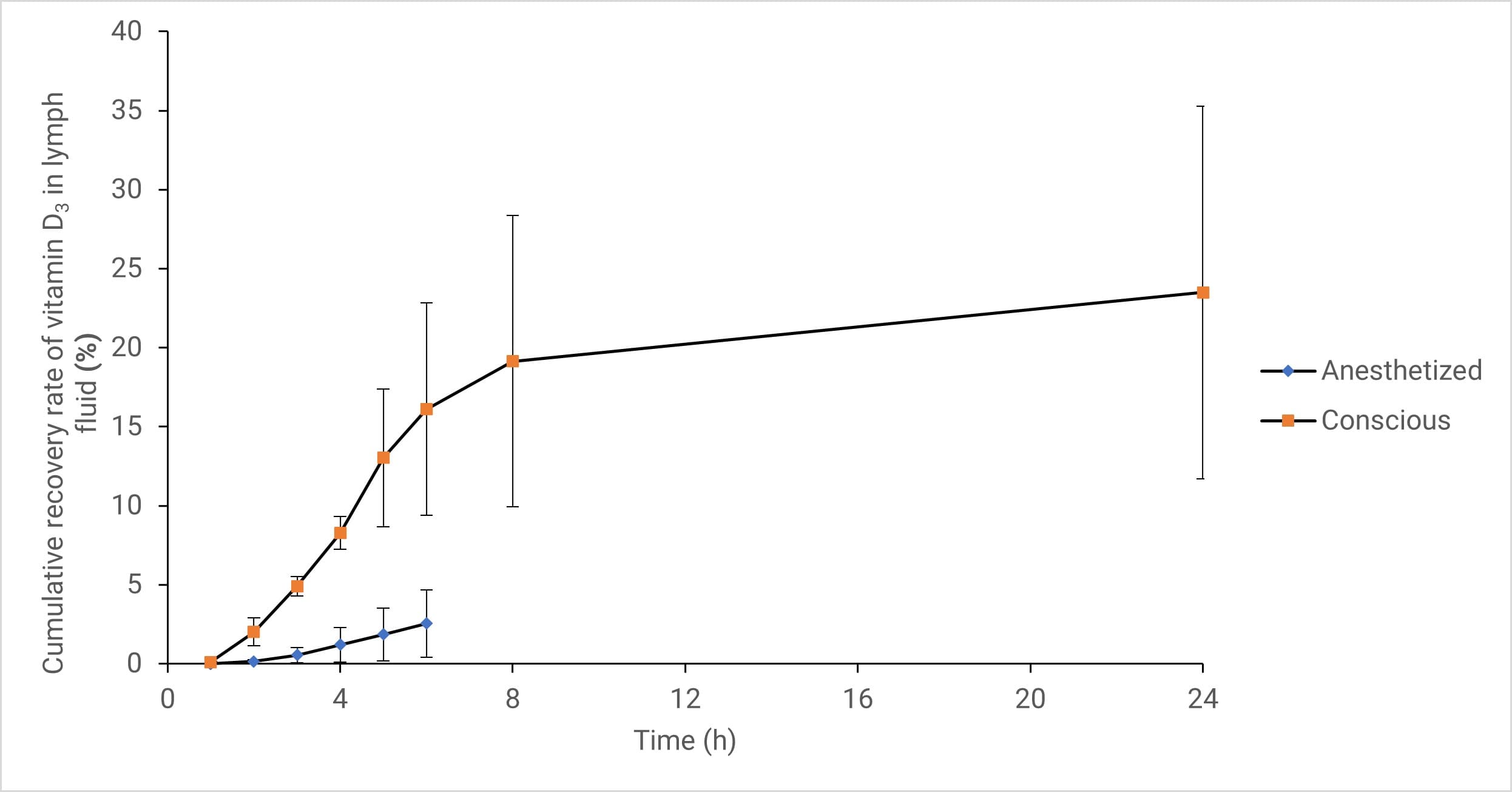

Figure 4. Cumulative recovery of Vitamin D3 in lymph fluid of anesthetized and conscious animal models (Data expressed as Mean ± SD, n=4)

Analysis of Vitamin D3 Results via Lymphatic Transport Pathway

Studies indicate that the transport pathway of Vitamin D3 was not obstructed by anesthesia across different experimental models. In the sham surgery group, the AUC0-8h values in plasma (representing the total drug absorbed via both lymphatic and non-lymphatic pathways) for conscious and anesthetized states were 6.5 and 4.8 µg·h/mL, respectively (see Table 3).

Simultaneously, Vitamin D3 lymphatic transport remained continuous in both states. Eight hours post-administration, the lymphatic transport dose for the conscious and anesthetized groups was approximately 12% and 9% of the administered dose, respectively. The lymphatic transport volume of Vitamin D3 in the anesthetized group decreased by approximately 25% compared to the conscious group [15]. Although anesthesia reduced the total absorption amount, the absorption pattern remained unchanged; thus, physiological processes involving different absorption pathways were not severely hindered.

Furthermore, using the anesthetized rat model simplifies the surgical procedure, speeds up the operation, and saves post-operative recovery time. Compared to the conscious model, the anesthetized model maintains higher patency of the lymphatic cannula and reduces the incidence of post-operative tube dislodgement. Therefore, for rapid screening of orally administered lymphatic absorption drugs, the anesthetized model is preferred. However, for exploring the absorption characteristics of specific molecules, the conscious model may be more appropriate.

Table 5. Relevant PK parameters of Halofantrine Hydrochloride in plasma under different experimental models

PK Parameter | Thoracic Duct | Mesenteric Lymph Duct | Portal Vein Cannulation | Non-Surgical |

Cmax (ng/mL) | 161.5 ± 43.2 | 183 ± 49.0 | 453 ± 227 | 383 ± 192 |

Tmax (h) | 20 ± 8.00 | 16.0 ± 9.24 | 8.00 ± 0.00 | 12.0 ± 8.00 |

T1/2 (h) | 36.7 ± 17.9 | 30.5 ± 2.67 | 64.1 ± 93.8 | 66.7 ± 19.0 |

AUC0-inf (ng.h/mL) | 11194.5 ± 5968 | 7083 ± 1908 | 21247 ± 10794 | 18815 ± 5249 |

MRT0-inf (h) | 61.8 ± 24.5 | 45.6 ± 6.68 | 77.6 ± 49.6 | 79.6 ± 14.7 |

Hepatic Extraction Ratio | N/A | N/A | 0.120 ± 0.106 | N/A |

Table 6. Recovery rates of Halofantrine Hydrochloride in lymph fluid under different experimental models

Mesenteric Lymph Duct | Thoracic Duct | |

Total Drug Recovery (ng) | 261917 ± 86024.78 | 531402 ± 107797.79 |

Total Recovery Rate in Lymph (%) | 11 ± 3.42 | 23 ± 4.76 |

Lymph Clearance (mL/min/kg) | 2 ± 1.11 | 4 ± 1.50 |

Analysis of Halofantrine Results:

Experimental results demonstrate that the choice of lymph collection site influences the evaluation of drugs absorbed via the lymphatic system.

Mesenteric lymph cannulation primarily collects drugs absorbed from the lower body and intestinal lymph.

Thoracic duct cannulation primarily collects drugs from interstitial capillaries, accounting for approximately three-quarters of the body's lymphatic circulation (see Table 5).

Differences in the scope of lymphatic circulation covered by various experimental models lead to slightly different evaluations of PK parameters related to lymphatic transport. Therefore, selecting an experimental model that matches the specific research objective is essential for obtaining accurate experimental feedback.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Drug absorption via lymphatic transport can bypass hepatic first-pass metabolism, thereby increasing the bioavailability of oral drugs. For drugs subject to strong first-pass metabolism, the lymphatic transport pathway is of significant importance, showing immense potential, particularly for the development and utilization of highly lipophilic, poorly soluble drugs. WuXi AppTec DMPK has successfully established relevant research models for rat lymphatic absorption to support pharmacokinetic studies and other research related to the lymphatic absorption pathway.

Authors: Furong Jiao, Xuan Dong, Yunxi Chen, Honglei Ma, Cheng Tang

Talk to a WuXi AppTec expert today to get the support you need to achieve your drug development goals.

Committed to accelerating drug discovery and development, we offer a full range of discovery screening, preclinical development, clinical drug metabolism, and pharmacokinetic (DMPK) platforms and services. With research facilities in the United States (New Jersey) and China (Shanghai, Suzhou, Nanjing, and Nantong), 1,000+ scientists, and over fifteen years of experience in Investigational New Drug (IND) application, our DMPK team at WuXi AppTec are serving 1,600+ global clients, and have successfully supported 1,700+ IND applications.

Reference

[1] Abdallah M, Müllertz OO, Styles IK, et al. Lymphatic targeting by albumin-hitchhiking: Applications and optimisation. J Control Release. 2020;327:117-128.

[2] Moore JE Jr, Bertram CD. Lymphatic System Flows. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 2018;50:459-482.

[3] Trevaskis NL, Kaminskas LM, Porter CJ. From sewer to saviour - targeting the lymphatic system to promote drug exposure and activity. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14(11):781-803.

[4] Sweeney MD, Zlokovic BV. A lymphatic waste-disposal system implicated in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2018;560(7717):172-174.

[5] Anatomy of the Lymphatic and Immune Systems.Anatomy and Physiology | OpenStax

[6] Chakraborty S, Shukla D, Mishra B, Singh S. Lipid--an emerging platform for oral delivery of drugs with poor bioavailability. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;73(1):1-15.

[7] Chai Xuyu, Tao Tao. Research progress on lipid-promoted intestinal lymphatic transport of drugs [J]. Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal, 2008, 43(22): 1681-1684.

[8] Trevaskis NL, Charman WN, Porter CJ. Lipid-based delivery systems and intestinal lymphatic drug transport: a mechanistic update. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60(6):702-716.

[9] Caliph SM, Trevaskis NL, Charman WN, Porter CJ. Intravenous dosing conditions may affect systemic clearance for highly lipophilic drugs: implications for lymphatic transport and absolute bioavailability studies. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101(9):3540-3546.

[10] Cense HA, van Eijck CH, Tilanus HW. New insights in the lymphatic spread of oesophageal cancer and its implications for the extent of surgical resection. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20(5):893-906.

[11] Karpf DM, Holm R, Garafalo C, Levy E, Jacobsen J, Müllertz A. Effect of different surfactants in biorelevant medium on the secretion of a lipophilic compound in lipoproteins using Caco-2 cell culture. J Pharm Sci. 2006;95(1):45-55.

[12] Seeballuck F, Lawless E, Ashford MB, O'Driscoll CM. Stimulation of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein secretion by polysorbate 80: in vitro and in vivo correlation using Caco-2 cells and a cannulated rat intestinal lymphatic model. Pharm Res. 2004;21(12):2320-2326.

[13] Kraft JC, Freeling JP, Wang Z, Ho RJ. Emerging research and clinical development trends of liposome and lipid nanoparticle drug delivery systems. J Pharm Sci. 2014;103(1):29-52.

[14] Banan B, Wei Y, Simo O, et al. Intestinal Lymph Collection via Cannulation of the Mesenteric Lymphatic Duct in Mice. J Surg Res. 2021;260:399-408.

[15] Dahan A, Mendelman A, Amsili S, Ezov N, Hoffman A. The effect of general anesthesia on the intestinal lymphatic transport of lipophilic drugs: comparison between anesthetized and freely moving conscious rat models. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2007;32(4-5):367-374.

[16] Brocks DR, Toni JW. Pharmacokinetics of halofantrine in the rat: stereoselectivity and interspecies comparisons. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1999;20(3):165-169.

[17] Khoo SM, Prankerd RJ, Edwards GA, Porter CJ, Charman WN. A physicochemical basis for the extensive intestinal lymphatic transport of a poorly lipid soluble antimalarial, halofantrine hydrochloride, after postprandial administration to dogs. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91(3):647-659.

[18] Porter CJ, Charman SA, Charman WN. Lymphatic transport of halofantrine in the triple-cannulated anesthetized rat model: effect of lipid vehicle dispersion. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85(4):351-356.

[19] Porter CJ, Charman SA, Humberstone AJ, Charman WN. Lymphatic transport of halofantrine in the conscious rat when administered as either the free base or the hydrochloride salt: effect of lipid class and lipid vehicle dispersion. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85(4):357-361.

Related Services and Platforms

-

In Vivo PharmacokineticsLearn More

In Vivo PharmacokineticsLearn More -

Novel Drug Modalities DMPK Enabling PlatformsLearn More

Novel Drug Modalities DMPK Enabling PlatformsLearn More -

Rodent PK StudyLearn More

Rodent PK StudyLearn More -

Large Animal (Non-Rodent) PK StudyLearn More

Large Animal (Non-Rodent) PK StudyLearn More -

Clinicopathological Testing Services for Laboratory AnimalsLearn More

Clinicopathological Testing Services for Laboratory AnimalsLearn More -

High-Standard Animal Facilities and Animal WelfareLearn More

High-Standard Animal Facilities and Animal WelfareLearn More -

Preclinical Formulation ScreeningLearn More

Preclinical Formulation ScreeningLearn More

Stay Connected

Keep up with the latest news and insights.