Covalent drugs contain specific functional groups that are designed to covalently bind to specific sites in target protein[1]. This binding induces a conformational change, inhibiting the protein's activity and disrupting its pathological function. In contrast to non-covalent interactions—such as hydrogen bonds, Van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic interactions—covalent bond dissociation requires significantly more energy. Therefore, covalent binding to target proteins is more durable. The formation of covalent bonds allows for complete target occupancy even at relatively low concentrations[2]. As a result, covalent inhibitors offer prolonged efficacy, reduced dosing frequency, and enhanced selectivity.

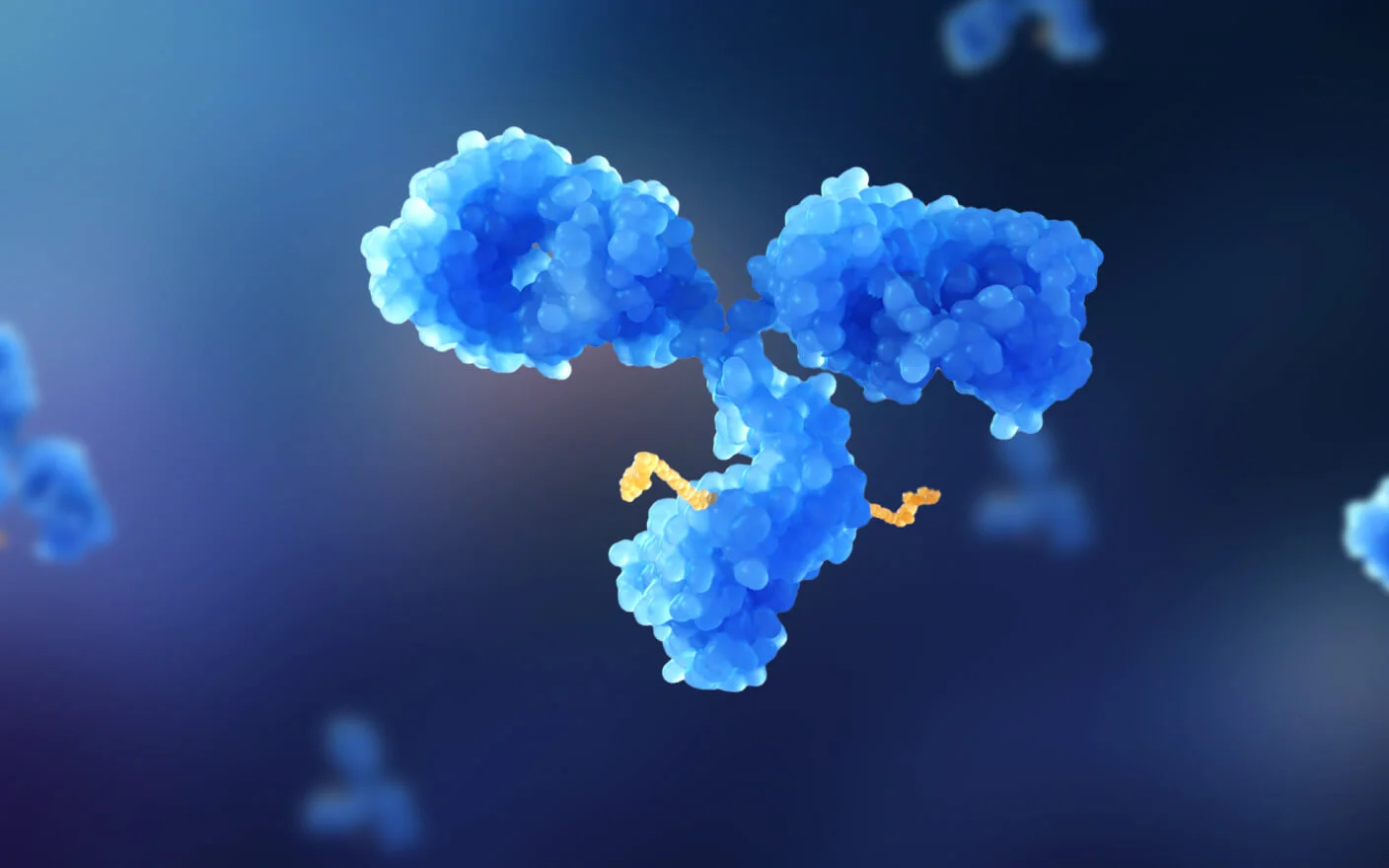

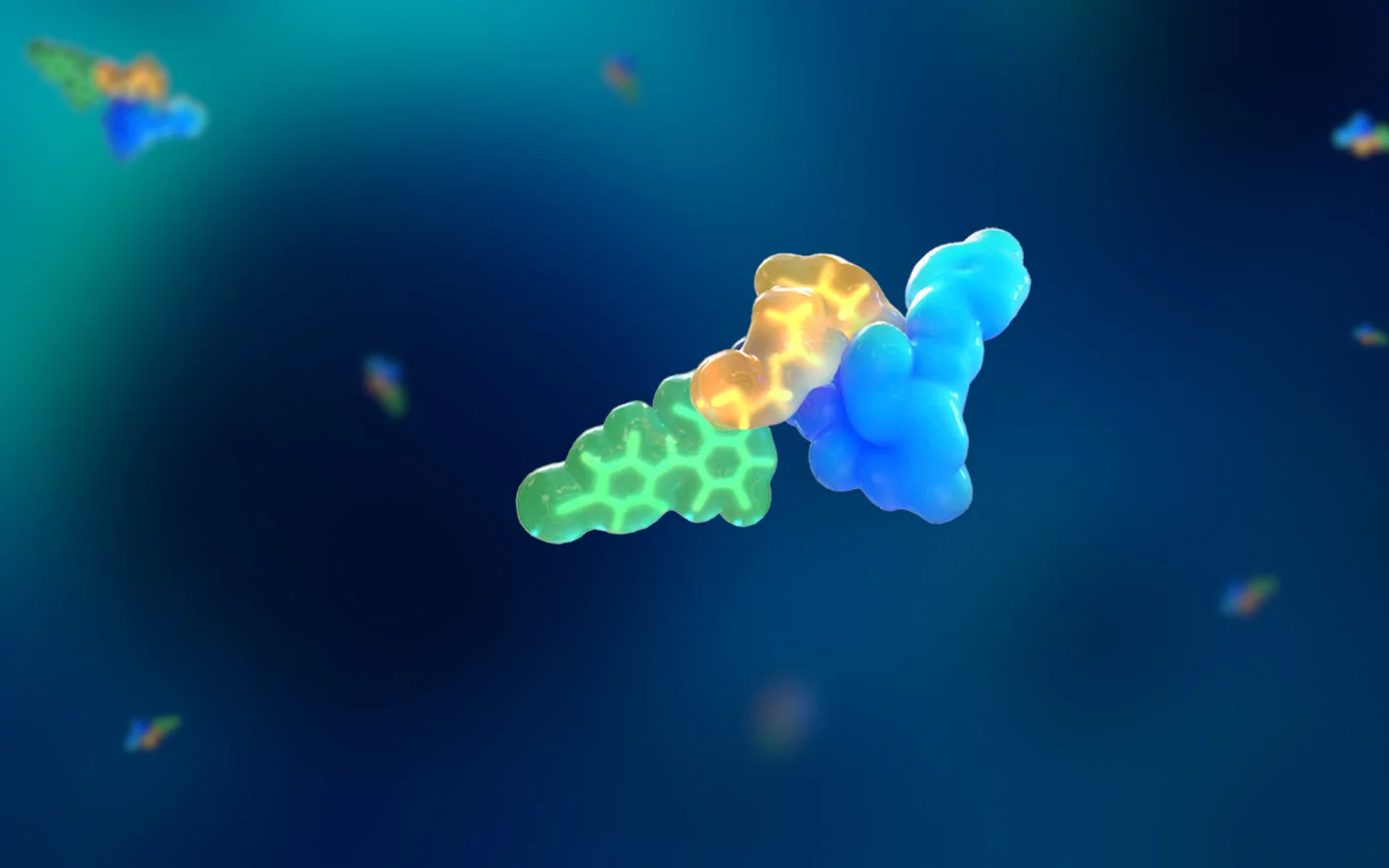

The formation and dissociation of covalent bonds represent a dynamic equilibrium process (see Figure 1). Initially, the inhibitor (I) binds non-covalently to the target protein (P), forming a reversible affinity complex (PI). Subsequently, I and P form irreversible covalent bonds (shown in red) at the binding site, resulting in an inactivated covalent complex (PI*). Most covalent inhibitors irreversibly modify their target proteins. The field of covalent drugs is rapidly evolving within drug discovery. This article focuses on the high-throughput screening and characterization platforms for covalent drugs, including high-resolution mass spectrometry screening and characterization platforms based on intact protein method, high-throughput screening platforms based on differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF), and binding characterization platforms based on peptide mapping.

Figure 1. Mechanism of covalent inhibitor [3]

Overview and history of covalent drug development

Since the introduction of the first covalent inhibitor in the late 18th century, the field has seen significant advancements. Currently, approximately 30% of marketed drugs are covalent drugs[4]. Many covalent inhibitors were initially discovered by chance and later demonstrated therapeutic effects through covalent binding. For example, aspirin and penicillin are well-known and widely used covalent drugs[5].

Aspirin is an irreversible inhibitor of cyclooxygenase, which acts by acetylating the active site serine residue to reduce the synthesis of prostaglandins, thereby achieving analgesic, antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, and antiplatelet aggregation effects.

Penicillin covalently binds to the active site serine of glycopeptidyl transferase, inactivating the enzyme and catalyzing the cross-linking of peptidoglycan chains during bacterial cell wall synthesis. This interference with peptide cross-link formation diminishes the bacteria's ability to resist penetration, ultimately leading to bacterial growth cessation or death.

Covalent drugs have undergone a series of developments from accidental discovery to "Reversible First" and then to "Electrophile First"[6] (Figure 2). The "Reversible First" strategy refers to the attachment of a reactive functional group (e.g., acrylamide) to reversible inhibitors. Based on this method, drugs such as afatinib, simertinib, and acalabrutinib have been successfully developed. The "Electrophile first" approach utilizes the reactive handle compound library (electrophile library) to screen and identify handles that form covalent bonds with specific amino acid residues of the target protein and can be used for undruggable targets. For example, the Kirsten rats arcomaviral oncogene homolog (KRAS) is a classic undruggable target characterized by shallow binding pockets, high affinity for natural substrates or cofactors, strong competition between inhibitors and substrates, necessitating high doses of inhibitors. Scientists found that mutant KRASG12C can be targeted by covalent small molecule drugs and successfully developed sotorasib and adagrasib. This marks the beginning of the third era in covalent drug discovery and the resurgence of targeted covalent inhibitors.

Figure 2. The progress of marketed covalent drugs[6]

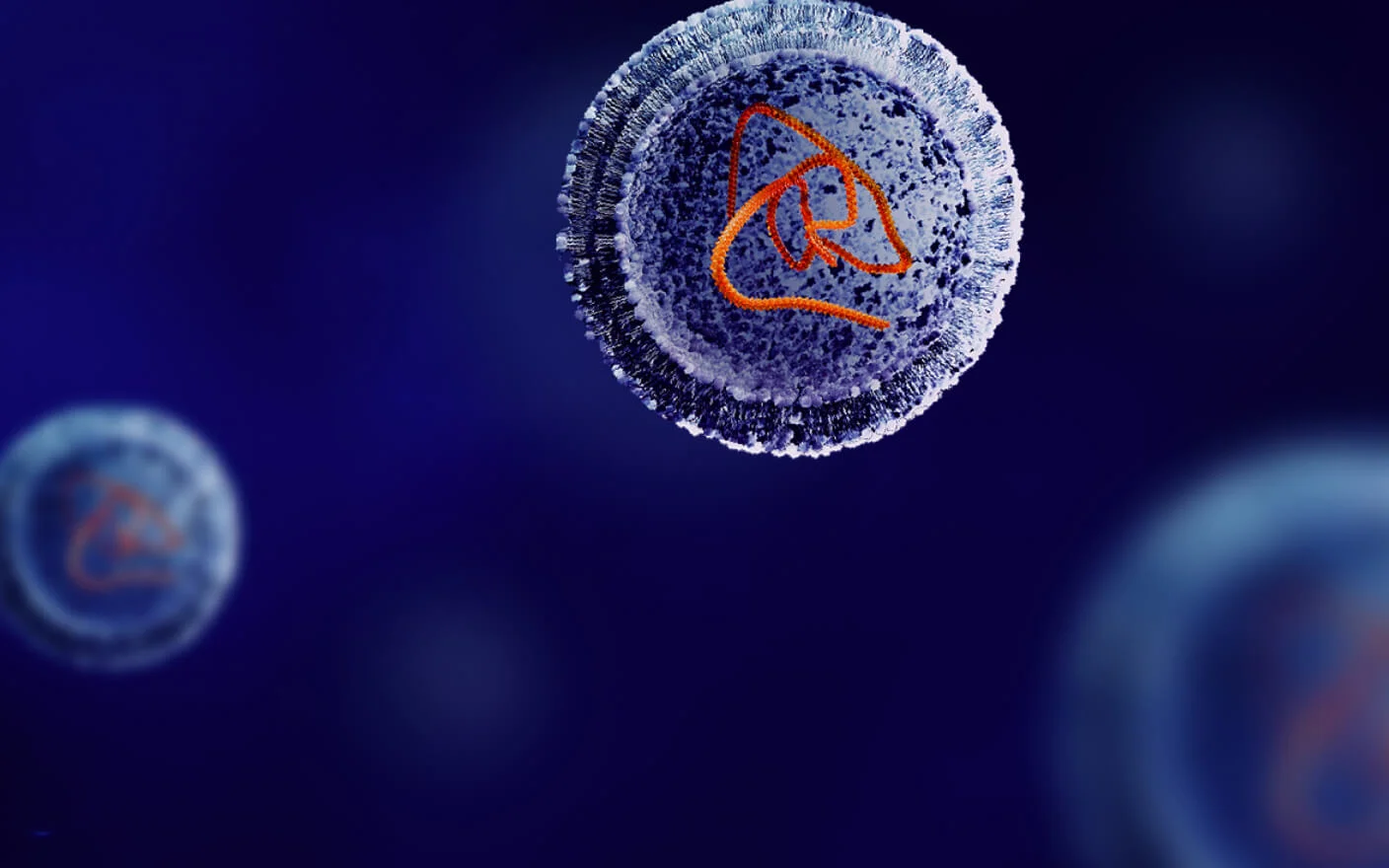

Beyond the direct inhibitors mentioned, two additional strategies inhibit the target protein directly through a covalent mechanism without relying on small molecules. One approach is targeted protein degradation. The most commonly used small molecule degraders are bispecific compounds called PROTACs (proteolysis-targeting chimeras), which use the ubiquitin-protease system to degrade target protein. One end of the PROTAC binds to the target protein, while the other end binds to the protease responsible for degradation. This proximity facilitates ubiquitination of the target, leading to its eventual degradation. The other strategy is molecular glue, a small molecule drug that can bring together two proteins that have not interacted with each other and create a new effect to block the function of the target protein.

In summary, regardless of the drug design mechanism, hit compounds must undergo validation and characterization before progressing to structural optimization.

Strategies for high-throughput screening and characterization of covalent drugs

High-throughput screening (HTS), DNA-encoded compound screening (DEL), in silico virtual screening, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) are commonly used in identification, discovery, and characterization of hit compounds. Each platform has its unique advantages. For a more comprehensive analysis, it is beneficial to use multiple platforms to cross-verify results.

Intact protein–high-resolution mass spectrometry screening and characterization platform

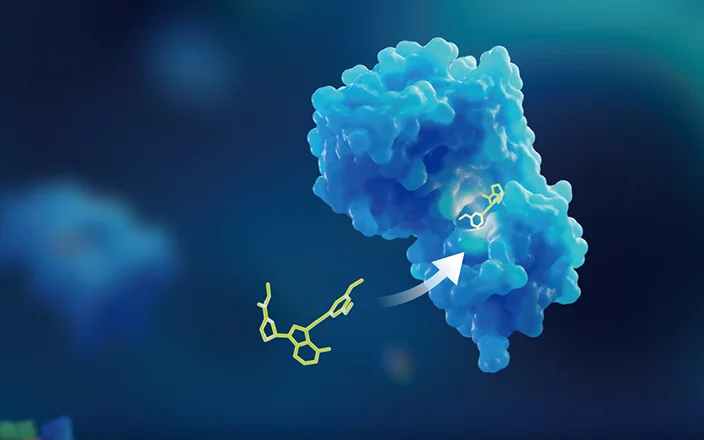

Mass spectrometry is widely used in covalent drug discovery. When compounds bind to a target protein, the protein’s molecular weight increases, allowing for precise measurement and monitoring of irreversible covalent bonds using HRMS. The method is simple to develop, offers high throughput, and demonstrates excellent reproducibility. As shown in Figure 3, we take KARSG12C and its inhibitor sotorasib as an example. The molecular weight shift can be observed after incubation. The mass shift is exactly the molecular weight of sotorasib. Under this incubation condition, KARSG12C fully combined with sotorasib with a binding rate of 100%. LC-HRMS can monitor the binding and calculate the binding ratio.

Figure 3. Intact protein results using LC-HRMS

Differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF)-high throughput screening platform

While MS methods are widely used for screening covalent drugs, increasing interest in the field has led to the exploration of additional high-throughput strategies to evaluate more compounds in less time. Differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) is a method to track the folding state and thermal stability of proteins [7]. DSF is commonly used in protein thermal stability studies, protein-ligand interaction studies protein stabilizers, and inhibitor screening studies. The principle of DSF is that as the temperature rises, proteins unfold, exposing hydrophobic regions that bind fluorescent dyes, resulting in an enhanced fluorometric signal. The data is fitted to the Boltzmann equation to calculate the melting temperature (Tm) of the protein (see Figure 4). Tm is defined as the temperature at which 50% of the protein sample is folded and 50% is unfolded [7].

Figure 4. Schematic diagram of differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) [7]

DSF is often utilized to detect the binding of small molecule ligands to target proteins[8]. In covalent drug screening, DSF can also monitor changes in protein thermal stability before and after binding.

When the covalent drug binds to the target protein, the stability of the target protein is enhanced, and the Tm increases. As shown in Figure 5, the blue line shows the state of the target protein. The purple line shows the state of the target protein binding to drug candidates. The difference in melting temperature between the two lines is expressed as (ΔTm) which can be used to evaluate whether the drug candidates bind to the target protein. The DSF method offers advantages such as low protein sample requirements, high throughput, and rapid analysis times, making it suitable for high-throughput drug candidate screening and target discovery.

Figure 5. Covalent binding of drugs induces protein melting temperature (Tm) migration

Peptide mapping-binding characterization platform

Peptide mapping is a key technique for determining the primary structure (amino acid sequence) of proteins and is commonly employed in the quality control of protein and peptide drugs[9]. Peptide mapping relies on high-resolution mass spectrometry and exhibits high sensitivity to identify end blocking or modifications in samples. In the screening stage of covalent drugs, peptides are analyzed by HRMS to identify which amino acid sites covalently bind to the protein. Peptide mapping can be used to elucidate the mechanism (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Schematic of Peptide Mapping Principles[10]

Figure 7 shows peptide mapping results of KRASG12C protein and its inhibitor sotorasib. After trypsin digestion, the sequence coverage reached 100%. Sotorasib covalently binds to cysteine in the peptide LVVVGACGVGK, with a retention time of 58.37 minutes and a confidence score of 100.

Figure 7. Peptide mapping of KRASG12C after covalent binding with sotorasib

WuXi AppTec DMPK offers high-throughput screening and characterization services based on high-resolution mass spectrometry and differential scanning fluorimetry (Figure 8), including conventional covalent drugs, molecular glues, PROTACs, etc. As well as a variety of in vitro and in vivo metabolic models (in vitro glutathione binding models), and metabolite identification studies. This involves the separation, analysis, and identification of metabolites within biological matrices to understand the metabolism and clearance pathways of covalent drugs, facilitating comprehensive evaluations.

Figure 8. DMPK covalent drug screening and characterization platforms

A final word

With extensive experience in high-throughput screening and characterization of covalent drugs, WuXi AppTec DMPK successfully established platforms based on intact protein, differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF), and peptide mapping. The advantages of these platforms include short method development times, high throughput, accuracy, and speed. We have accumulated extensive research experience in covalent drug analysis, in vitro ADME, in vivo metabolite identification, and radioactive ADME research, thus providing integrated solutions to partners. Currently, we have successfully supported over 100 covalent drug projects and supported many covalent drugs entering the clinical stage.

Authors: Li Qu , Rui Wang, Yongjing He, Hongmei Wang, Zhiyu Li , Lili Xing

Talk to a WuXi AppTec expert today to get the support you need to achieve your drug development goals.

Committed to accelerating drug discovery and development, we offer a full range of discovery screening, preclinical development, clinical drug metabolism, and pharmacokinetic (DMPK) platforms and services. With research facilities in the United States (New Jersey) and China (Shanghai, Suzhou, Nanjing, and Nantong), 1,000+ scientists, and over fifteen years of experience in Investigational New Drug (IND) application, our DMPK team at WuXi AppTec are serving 1,600+ global clients, and have successfully supported 1,500+ IND applications.

Reference

[1] Lonsdale R, Ward R A. Structure-based design of targeted covalent inhibitors[J]. Chemical Society Reviews, 2018:10.1039.

[2] Adeniyi A A, Muthusamy R, Soliman M E. New drug design with covalent modifiers[J]. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery, 2016, 11(1):79.

[3] Li K S, Quinn J G, Saabye M J, et al. High-throughput kinetic Characterization of Irreversible Covalent Inhibitors of KRAS(G12C) by Intact Protein MS and Targeted MRM[J]. Analytical chemistry, 2022(94-2).

[4] Sutanto F, Konstantinidou M, Dmling A. Covalent inhibitors: a rational approach to drug discovery[J]. RSC Medicinal Chemistry, 2020,(8):11.

[5] Zhang T , Hatcher J M , Teng M ,et al. Recent Advances in Selective and Irreversible Covalent Ligand Development and Validation[J]. Cell Chemical Biology, 2019, 26(11).

[6] Lucas S C C, Blackwell J H, Hewitt S H, et al. Covalent hits and where to find them[J]. SLAS Discovery, 2024(3):29.

[7] Bruce D, Cardew E, Freitag-Pohl S, et al. How to Stabilize Protein: Stability Screens for Thermal Shift Assays and Nano Differential Scanning Fluorimetry in the Virus-X Project[J]. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 2019(144).

[8] Ito S, Matsunaga R, Nakakido M, et al. High-throughput system for the thermostability analysis of proteins[J]. Protein Science, 2024,33(6):e5029.

[9] Kuril A K, Saravanan K. High-throughput method for Peptide mapping and Amino acid sequencing for Calcitonin Salmon in Calcitonin Salmon injection using Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-HRMS) with the application of Bioinformatic tools[J]. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 2024,(243)116094.

[10] Mons E, Kim R Q, Mulder M P C. Technologies for Direct Detection of Covalent Protein–Drug Adducts[J].Pharmaceuticals, 2023,16(4), 547.

Related Services and Platforms

-

DMPK BioanalysisLearn More

DMPK BioanalysisLearn More -

Novel Drug Modalities DMPK Enabling PlatformsLearn More

Novel Drug Modalities DMPK Enabling PlatformsLearn More -

Novel Drug Modalities BioanalysisLearn More

Novel Drug Modalities BioanalysisLearn More -

Small Molecules BioanalysisLearn More

Small Molecules BioanalysisLearn More -

Bioanalytical Instrument PlatformLearn More

Bioanalytical Instrument PlatformLearn More -

PROTAC DMPK ServicesLearn More

PROTAC DMPK ServicesLearn More -

ADC DMPK ServicesLearn More

ADC DMPK ServicesLearn More -

Oligo DMPK ServicesLearn More

Oligo DMPK ServicesLearn More -

PDC DMPK ServicesLearn More

PDC DMPK ServicesLearn More -

Peptide DMPK ServicesLearn More

Peptide DMPK ServicesLearn More -

mRNA DMPK ServicesLearn More

mRNA DMPK ServicesLearn More -

Covalent Drugs DMPK ServicesLearn More

Covalent Drugs DMPK ServicesLearn More

Stay Connected

Keep up with the latest news and insights.